Sometime in middle-late 2021, we’re walking the dogs, Emma and I, around the dog park: one of those little pandemic walks. We talk about being in our mid-thirties, her 34 or almost, me 33. Everyone says do it before you’re 35. We’re thinking about it. Actually, Emma’s already pregnant, although I don’t know this yet. It’s still a little secret just for her and her partner. I tell her to read a book I’ve recently read: The Panic Years, by Nell Frizzell. I didn’t particularly like it or relate to it, but I recommend it all the same. Homework. This is what I do now: I study for a test I don’t know if I even want to sit – a test that Emma, unbeknownst to me, has already aced.

I’m not ready. Maybe in a couple of years.

Then it’s December and Emma’s told me the news, and suddenly I’m doing calculations, pulling up my period tracker app, coming up with a timeframe. I run it past Murray, though it’s less collaborative than it should be. I’m older than he is, and anyway I think if we don’t do it now I’ll chicken out and will never want to do it.

I buy prenatal vitamins on the 1st of January: rebirth, etc. My rubella levels are on the fence; I schedule a booster shot.

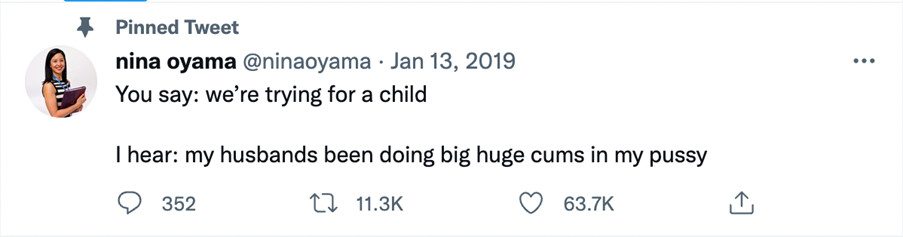

It happens on the first try. Try. We were trying. Every time I hear that phrase I think about that tweet, Murray tells me, you know the one?

There’s a few days in early February, almost a week, of peeing on a stick and seeing the second line; sending photos to Emma and my sister for analysis. I haven’t even told Murray yet. I’m waiting to be sure, except I already am – I was sure before I even saw the first stick, in a way that had nothing to do with reason or physicality, in a way I couldn’t and still can’t explain. I keep waiting to freak out – to feel that sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach, to realise this isn’t what I wanted – but every time I see the faint second line, I’m calm. Pleased. (What would I have done otherwise? Taken care of it, maybe, by myself. Told Murray it hadn’t worked, that maybe we should just get another dog or something.) Somehow it’s happened, the thing I didn’t think would ever happen: I’m ready.

What changed? Emma asks me when I tell her this. I shrug. You getting pregnant, probably, I say. Like: people like us can do this. Or maybe I just didn’t want to be first. I don’t know how to explain it. No, that makes sense, Emma says. It’s like in that book you told me about, The Panic Years? The odds of getting pregnant drastically increase when your friends start having babies. It’s, like, science.

Had that been in the book? I’d forgotten.

That was February.

The first trimester passes fairly quickly. It’s fun, it sucks, it’s weird, it’s not real – still a secret, mostly. I’m nauseous but it passes whenever I eat something, so I’m constantly eating, even though I’m not hungry. I need to sleep so much I’m incapable of little else: I can feel my energy being drained from my body. At some point, my gums start to bleed every time I brush my teeth. This is what it is to have a parasite living inside of you. It’s a horror movie, some sci-fi shit, and also the most boring thing in the world. We were all parasites to our own hosts, once.

Luckily I don’t vomit, at least not much; maybe only once or twice. I keep waiting to feel it: that oh-shit-what-have-I-done feeling. It doesn’t come. A relief.

Then, the second trimester, out of nowhere: oh shit. What have I done.

Suddenly it’s September. How are you feeling? everyone asks. How does it feel? It feels like I’m throwing a funeral for my own body, a funeral nobody else is invited to. But you can’t say that. I say what you’re meant to say: Oh, you know! A little laugh. Ready, not ready. Scared shitless. We have no idea what we’re doing! Another little laugh. Oh, no one does, no one does, everyone says. You’ll figure it out! Conversations like this bore me, the ones you have before you’ve even had them.

A funeral for my perfect perky boobs, those cute plump nipples and rosy pink areolas! When I was seventeen I watched an episode of Oprah. They’d discovered the perfect breasts – science had, or Oprah; somebody had anyway. They put a photo up on the screen: these were them! The fabled perfect boobies! Small but pert, enough to hold onto but not encumbersome; manageable. Would you understand what I mean if I told you they were…boyish, somehow? But still feminine: demigirl breasts. I gasped. Those were my boobies! Like looking in a mirror. An Oprah’s Book Club sticker for my chest, what higher honour?

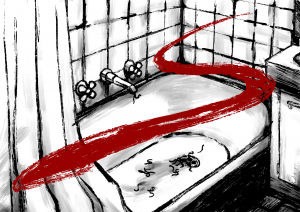

Now they’re too big, much too big, so lumpy, body dysmorphia for the first time in my life, this isn’t who I am, this maternal body forced upon someone who is still trying to navigate the word mother, not quite sure about woman either if we’re being honest. They’re starting to droop a little, like a dying plant. I google: is it normal pregnancy areolas different colours from each other? One’s a dark grey-brown purple, the other a lighter dusty purple-pink. I call Murray into the bathroom, under the harsh light: am I seeing things? Nope, he says, definitely different. Huh.

I google: is it normal to feel gross about breastfeeding your baby? Like…you know. All the straight people tell me the weirdness goes away, that it’s not an issue by the time you actually have to do it. But I’m not convinced. This is why I need a queer community of birthing parents, those who know what it is to have and to hold.

Anyway, rest in peace to the Oprah’s Book Club recommendation of boobs. I’ll pour one out for you, at this funeral nobody’s invited to. Sláinte.

How many times had I sat in front of how many therapists, trying to explain that I both did and did not want children, that the thing I feared most was the label: mother. Or maybe being seen as mother, being perceived as “woman”. It’s not that I’m, like, confused, I’d say, even though I guess I was. It’s not that I don’t feel like a girl. (That part was true.)

What changed? Emma had asked in February. Maybe giving myself permission to be more than just what I am.

Another drooping, dying plant, this time a real one: a couple of years ago, back in early 2020, I’d began renting a little writing studio above a local café. An extra monthly expense, but cheap as far as studio spaces went. A desk, bookcase, the old Ikea armchair with the huge hole in the cushion from when Patti was a puppy. I strategically arranged a blanket over the top of it so you couldn’t see the hole. I bought and carried up Sydney Road a hardy plant from Bunnings to put in the corner, one that didn’t need too much from me. A little water, now and then. The light that came in through the clear polycarbonate roofing, which let the possum poop in and leaked after a bad storm.

Now Xanthea’s moving out of our other bedroom to make room for the baby, and I can no longer afford to keep paying rent on the little room I’m barely using. I have to give it up. We go and clear it out – well, Murray does; dissembles the desk, carries down boxes of my books, the bookcase, the chair.

The dead or dying plant. I haven’t been able to get to my studio; I’m too large, too sick, too exhausted. I’ve barely been writing at all. Even the hardiest plants need more than you think.

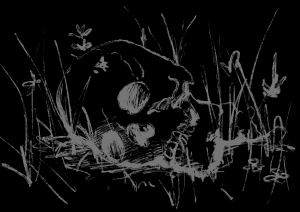

A funeral for that plant, and if I were prepared to think about what it represented, the obvious metaphor of it blah blah blah I’d mourn that too. But I’m not prepared to think about it: only to write around it. I look the other way. The plant sits deserted in the backyard now, on the brink. I should repot it, but I’m not allowed to garden in my condition – something about the chemicals. Another metaphor?

Now I write in the room that was not so long ago my housemate’s bedroom and will soon be a nursery – a different sort of bedroom for a different sort of housemate, one who does less dishes and does not pay rent and is a terrible conversationalist.

On one side of the room: the green iMac I bought for my studio after I got my tax back, a remnant of a more hopeful time. A stack of novels much better than the one I’m trying to write, a handful of crystals from another time I was desperate for anything that would help get the words down: carnelian for motivation, citrine for clarity and willpower, amazonite for creativity and truth-telling. I pad into the room in my plush slippers and write, ignoring the other side of the room: the cot that is not built and the overflowing bags of op shop baby clothes that my mother the forager has sent down from Brisbane, and the bassinet and leftover baby diapers and adult diapers and nursing pads and manual breast pump that Emma gave me, darling Emma, the only friend I have who knows what’s coming. The separation between the two sides of the room: writing and baby. These metaphors are all so obvious they’re boring. Am I boring you?

At night, straddling my incredibly annoying giant pregnancy pillow, I fantasise about fucking a famous actress. She’s almost a decade younger than I am; voluptuous, blonde, great smile. I fantasise about impregnating her, which I don’t need a therapist to tell me is probably about trading places in some symbolic way, about unobtainable youth, transference. (Sometimes I get annoyed, tell Murray: why can’t you just be a girl so if we want to do this again, I don’t have to be the one to do it?)

In the hospital we’re put in boxes, all of us women, even the ones who aren’t, or aren’t entirely. It’s tidier this way. How are you doing, Mum? Who is “Mum”? I don’t know how Mum’s doing but Sian just wants some ibuprofen and a bath as hot as Hades and a one-litre bottle of red wine. To be able to go running again, to push her body beyond its limits in a way that has nothing to do with anyone else, a way that’s just for her. Like in the Back to the Future photo, “you” starts to disappear.

…But it’s kind of pleasant, too? The disappearing? In the hospital everything is pink, everyone so nice. A cisgender fever dream. A volunteer brings me a cup of water on my first visit. Is there anything else she can get me? By me she means: the host, the incubator, the baby-carrier. Does anyone here care about me, me-me? Not really, but table service in a hospital waiting room! I’ve been in and out of hospitals and doctors’ offices and specialist appointments my entire adulthood; being treated so well here is disorienting. I can be “Mum” if that’s what it takes to experience first-class healthcare. “Mum”, in a way, is a child herself, someone to be tended to. I agree to the whole deal, happily sign the contract: I’ll take care of them (poking the stomach) and you can take care of me, and somehow, this will all work out. In the meantime, call me whatever you want.

I tell my psychologist that I’m doing too much: my life is appointments, I’m so frazzled. She instructs me to do less. I tell my psychologist I’m barely leaving the house; I haven’t seen my friends in months (do I have any?) and she tells me to do more. We’re both flying by the seat of our pants.

On Tuesdays, at the local baths, I swim slow afternoon laps in the inside heated pool next to old men who have probably been ordered there by their physiotherapists. My hairy, tattooed, bulbous body in my red one-piece maternity swimsuit looks like a Baywatch Halloween costume. I feel proud of it, this huge, unsightly body. I swim freestyle for a lap, then breaststroke, then backstroke. My mother’s voice singing to me as an infant in the bathtub, returning to me now as though I’m watching a home movie: I can do the backstroke, breaststroke and the crawl. Look at me, look at me, I can do them all.

My body is something monstrous, which means of course that it’s something so completely banal, coded female, coded mother. At night I rub a balm into the flesh of my stomach, feel the ridges, almost welts, where the skin has stretched. There are purple-red lightning strikes all over my lower belly; looking at myself in the mirror naked feels like looking at the site of a vicious attack. The boys in my family all shoot up like beanstalks in puberty: the passed-down genes of our tall dead Dutch grandfather. Their bodies develop these same welts on their back from growing too fast. Once, my aunt was hauled into her son’s school principal’s office, accused of flogging my cousin. I’ve grown to love the beautiful, monstrous welts: my own inheritance.

There’s that whole thing about how every seven years, your cells replace themselves, so that the body that you had seven years ago is never quite the same one you have now. What’s happening now feels like a version of that on speed, and as I get closer I mourn the body that has been carrying me for 34 years, because I know that it is about to die its own sort of death in the act of bringing someone else’s body into the world. This is what your body was made for, people tell me – but as I almost fall over trying to get into my pants every day, as I struggle to stand for as long as it takes to do the dishes, as I consider the absence of my ankles (another death) I think: can this be true?

Now if someone were to ask me how I am, I’d tell them the truth: I feel as though I’m having a funeral for my body, and the only person who is invited hasn’t turned up yet.

More from Sian Campbell

READ ANOTHER IN THE SERIES

💀

ATTEND THE FUNERAL

Feature illustration by Morgan Thomas