Sometimes the only thing I can hear is the sound of my keyboard. A rapid-fire machine gun one minute, then slow as a dripping tap the next. More often than not, there is only silence: a pervading quiet.

I want to talk about the hush that enfolds my world. Before I do, please note I am not a famous novelist or author; I am a poet and freelance writer. The following commentary is born from my experience this past year living, more often than not, solely on my words. I’m writing this simply because I wish this advice existed years ago, when I was first starting out.

For whatever reason, it remains largely unsaid: that one of the things you need most as a writer is to be comfortable with silence. While skilled storytelling, a facility with language, and a ventriloquist’s ability to capture many voices are all good things to have, even more important is being able to live in the quiet.

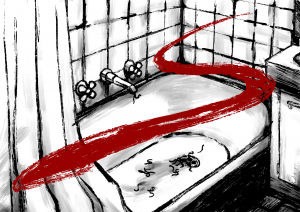

You need to be at home in yourself, with your own thoughts. That sounds kind of nice, even refreshing, right? You might be thinking, I’m so busy all the time, a moment to myself would be pretty great! The thing is, as a full-time or even part-time writer, it won’t be momentary – it’ll be constant – and you’ll be spending a great deal of time alone in a room with your anxieties, your doubts and insecurities. You need to get comfortable with the silence that holds all those things, and you need to do it before the quiet gets suffocating. This void will extend all around you to create a buffer zone – whether you intend it or not.

You’ll see your friends less often, despite your insistence that you’ll find the time. You will have less time for your lover(s), or less time to find one if you are unlucky enough to be single at the time this disease comes into its own, taking terminal root in your body. In this buffer zone, those fears and internal aches I mentioned will seem exponentially louder and will be much more damaging than you anticipate. On the plus side, if you can withstand that, you’ll come out the other end with a much more intimate understanding of your own personal monsters.

Mastering yourself is only part of the equation, however. The silence manifests in other ways. You’ll be sending your work out into the world, little shards of you, and more often than not silence will be your reward. This will be a silence that cuts, a silence with edges. This isn’t about rejection, it’s about the period that comes before: the interminable waiting, the never-knowing. Whether or not you’re working on something new while your articles await judgement, it will always be in the back of your mind that you have completed work which needs to find a home. Nor can you move on with it until each port of call responds, saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or worse, ‘maybe later’. It gnaws at you, this constant uncertainty, so much so that rejection is often a blessed relief – a release from the silence, however temporary.

While skilled storytelling, a facility with language, and a ventriloquist’s ability to capture many voices are all good things to have, even more important is being able to live in the quiet.

The silence, though, always returns. You are never going to be without it: whether it’s because you’re in the middle of a , or you’ve put a dozen things out there and are waiting several months for a reply. Whatever it is, the silence will come in spurts or in torrents, like rain. It is a fundamental part of a writer’s world. Now, if you are a person of colour, a queer writer, non-cisgender or fluid other – anybody who doesn’t fit into heteronormative white space – this experience is so much worse, so much harder to deal with, and so much more oppressive. Some days it will take on a physical weight, a silence like mountains, and crush you flat so you cannot even lift your head.

I wish I could tell you how to deal with this, but I’m still trying to figure it out. It’s going to set your whole body aching, I can tell you that much. Because you’ll be trying to be seen, and no one will want to see you. Because you’ll be trying to get heard, and no one will want to hear you. Because you’ll be trying to get paid, and no one will want to pay you. Sometimes, it will work out: you get approached or you do the approaching, there’s a brief flurry of exchanges and edits, then nothing. The silence, again. No one told me I would have this constant shadow following me around, a hushed veil through which the roar of the world is filtered into a muffled whisper.

It’s not all bad, as I mentioned. One of the advantages of getting to know yourself so well is that others seem distant and close all at once – it becomes harder to reach out, but easier to connect once you do. That might sound odd but think of it like this: it’s much simpler and safer to guide someone to a soft landing when you know the terrain better than anyone else. It’s getting through to the other side of silence – where this understanding lies – that is so difficult.

Nor is there an easy source to blame. Other editors and writers are grappling with their own strangling quiet, all of us only able to talk when we come up gasping for air – which is to say, infrequently. There’s a reason communication in the arts is so abysmal, and this lies at the heart of it: our sea-sawing mental health, the endless anxiety born of uncertainty, of not knowing when the next check is coming or where the next piece will end up if it ends up anywhere at all.

Too often, my room is a void and I feel this oceanic pressure against my ears, so I throw open my window just to hear the neighbours’ arguments on the wind, or the thrashing of trees, or the angry buzzing from wasps who have built a nest in the bricks of my home. Sometimes, even that is not enough. Because the silence is born of me, and nothing will satisfy it until I put fingers to keyboard and fill my room with beautiful noise.