Every couple of months, we ask an Australian author to read a book of their choice and reflect on it. Here’s their response.

Let me preface this by saying that I have no respect for authenticity when it comes to food. Don’t care, not interested, just feed me already.

I should also confess that I never use cookbooks. Most of the time, I cook by feeling, making slight variations to a series of vague formulae that I’ve memorised – a 3:3:1 ratio for flour, sugar and fat in a cake, for instance. When I do refer to recipes, I prefer to use the web, and my usual process is to skim half a dozen recipes from different websites so I can triangulate the common denominators, and then proceed with the laziest version possible. I’m not sure if that makes me a poor candidate for reviewing this, or the ideal critic. Who better to assess a cookbook on Jiangnan cuisine than a hard-to-impress Shanghainese Melburnian who judges recipes based on whether the results are tastier than plopping some frozen sticky rice shaomai in the microwave?

I’m writing this in May 2022. Shanghai has been in hard lockdown for more than a month. The city’s 25 million residents have been stuck in their flats, surviving on government rations supplemented with wholesale orders co-ordinated and delivered by neighbourhood volunteers. Some pass the time by posting flatlays of their rations and meals. Meanwhile, the delivery workers keeping the city alive – mostly domestic migrants – are sleeping on the street, in their trucks, or in makeshift camps, cooking instant noodles on camp stoves.

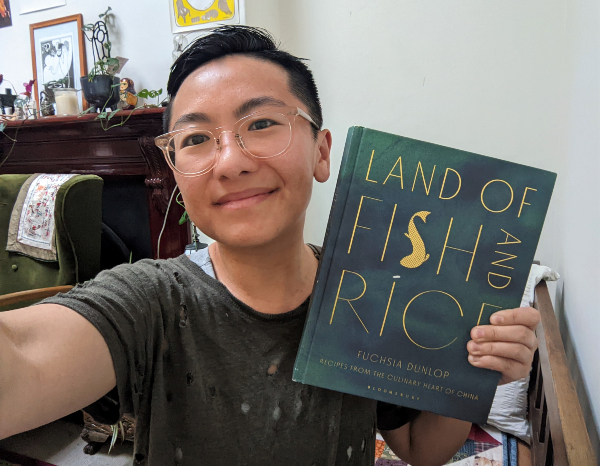

It’s an entirely different reality from when I was last there, pre-pandemic, and enjoying all the perks of a proper metropolis where you could get pretty much anything 24/7. Now it seems almost in poor taste to attempt hometown banquet cooking from the privilege and plenitude of my Footscray flat, some 8,000 kilometres away, but here we are. Shanghai’s on rations and I’m cooking my way through Fuchsia Dunlop’s recipes.

The Jiangnan region (literally ‘south of the river’) sits in the middle of China’s eastern coastline, where the Yangtze River meets the sea. If you imagine China as a rooster, Jiangnan is the front of the tummy – literally the belly of the beast. It’s been the most populous and prosperous part of China for over 1000 years.

First impression: it’s a handsome book. The gold and teal cover reminds me of celadon table settings in fancy teahouses, and the photos of Jiangnan’s wispy rivers and willow-fringed lakes make me desperately homesick. Fuchsia Dunlop is very well-regarded in both foodie and China-watching circles, and while I was a tad sceptical about Englishwoman’s take on my ancestral cuisine, there is undeniably something of substance here. Her writing is evocative (‘flavourful’, you’d say in Chinese), entertaining, and knowledgeable – the Oxbridge education was obviously not for nothing.

A strength of the text is Dunlop’s commitment to research, citation and attribution. Regional cookbooks can be annoyingly ahistorical, trading on the bucolic fantasy of timeless and anonymous folk traditions, but that’s not the case here. Her introduction offers a quick history of Jiangnan cuisine that considers how the region’s culinary evolution intersects with its politics, literature, and philosophy. She acknowledges the wealth of indigenous gastronomic writing from Yuan Mei’s 18th-century cookery book right back to Tao Yuanming’s 4th-century poems and highlights the playful lyricism in the naming of dishes. Many of the recipes presented are attributed to specific contemporary chefs or restaurants, and often they come with charming anecdotes and trivia.

For instance, Dunlop writes that a Ningbo dish of slow-cooked turtle is named ‘Grasping the Turtle’s Head’ in reference to a brilliant scholar who ate it on his way to take the imperial civil service examinations in Beijing, as each year, the top scholars would receive their honours standing next to a marble turtle sculpture on the palace steps. And a recipe for hongshaorou with eggs comes courtesy of the Dragon Well Manor restaurant in Hangzhou, along with a folk story that a mother made the dish for her son to welcome him home after the imperial exams, but he was delayed on his return. She reheated the stew the next day, and again on the third day, when he finally arrived home to a pot of thrice-cooked stew that was especially thick and tender. It’s staggering how many dishes have a connection to the imperial examinations that were fundamental to the fantasy of meritocracy in China for over a millennium. No wonder I still have nightmares about exams today!

Land of Fish and Rice offers a thoughtful and fairly representative selection of classic recipes from across the Jiangnan region, including some that you rarely see on restaurant menus, and a decent array of vegetarian options. There are some notable omissions – the crisp/creamy potato and apple salad and hearty beef and tomato soup that are the legacy of Shanghai’s once-strong Russian community, and zongzi, the real star of Dragon Boat Festival – but mostly her picks jive with my palate.

Dunlop’s scholarly approach results in a rather flattering portrait of the Jiangnan region as the enduring homeland of taste, sophistication and classical Chinese culture, where tender-hearted literati enjoy fine things in moderation while composing odes to friendship. Words like ‘gentle’, ‘seductive’ and ‘elegant’ pepper the text. It’s perhaps how we would like to imagine ourselves, and it certainly piques my pride and nostalgia, but it feels like a stretch for Jiangnan today. Hangzhou and Suzhou might still be heaven on earth, but they’re also cities of more than 10 million residents. While it’s true that people still cure their own pork on the pavement, I always worry whether the passing motorcycle fumes are a hazard. I would have liked more of a sense of contemporary China, and the culinary innovations of the recent past.

But the main problem I had with this book was simply that it’s not very practical. The recipes don’t give an estimate of cooking time or serving size,[i] and a few times I was caught out with an instruction buried halfway down the page to marinate something for a few hours or overnight. Variations are presented as paragraph text, even if they involve a whole new set of ingredients, and there are no photographs of techniques or ingredients, only the finished dish. That meant searching every aisle at Footscray KFL for xuecai or snow vegetable, which I had thought would come in a foil packet like other pickled greens, before I finally found it in a tin.

I live alone, and my friends and family have a variety of dietary needs (diabetic, lacto-vegetarian, halal, wheat-free), so I found it a bit frustrating that the layout and index provide no shortcuts if you want to find recipes suitable for specific diets, or a quick weeknight meal, or cooking for one. I know I’ve been spoiled by the tag-based searchability of websites, but ease of use is pretty essential for a cookbook. And if I didn’t have some baseline familiarity with the ingredients and flavours from eating Jiangnan cuisine my whole life, I think I would have found the book even more difficult to use.

Take the recipe for stuffed tofu skin parcels on page 59, for example. This dish is filed in the ‘Appetizer’ section alongside many non-vegetarian recipes, while a similar recipe for stuffed tofu skin rolls appears on page 175 under ‘Tofu’. Go figure. Then, the stuffed parcels are presented as a variation of another dish without stuffing, so there’s no ingredient list – you have to read the whole two-page recipe to figure out what you need. The recipe instructs you to reserve the soaking liquid from dried mushrooms, but never tells you what to do with it.

After forming my multi-layered tofu parcel, I couldn’t figure out how to deep-fry this long, damp, heavy log without burning my face off, so I decided to roast it instead. It actually turned out quite well, but I was baffled as to why Dunlop didn’t suggest that as an option. Households in China typically don’t have ovens, but surely her Anglophone readership mostly live in countries that do. Instead, the book sticks closely to the tools of a traditional Jiangnan kitchen (wok, pot, steamer, cleaver) with few mentions of ovens, microwaves, or even rice cookers.

The rigor of the scholarship here shields Dunlop from straying into the empty-headed nostalgia that’s all too common in regional cookbooks, but it still feels as though romantic, rustic aesthetics take precedence over practical considerations.

That left me wondering, who is this for? I had assumed that the core audience for an English-language book on Jiangnan cuisine would be people like me – diasporic Jiangnan illiterati who crave down-home cooking but need more precise tutelage than their families can give. But the book leaves out a lot of the features that would make it more user-friendly for cooks outside China, such as an illustrated shopping guide, more advice on ingredient substitutions, better accommodation of different dietary needs, and more attention to convenience. The fact that the Pinyin in the book doesn’t come with tone marks, and there’s nothing in Wu, the main language of the Jiangnan area, reinforces the feeling that this isn’t written with the diaspora in mind.[ii]

As I made my way through Land of Fish and Rice, I found myself reaching for Google to fill in the gaps the book left. More often than not, I ended up on the same websites I usually go to – The Woks of Life, Omnivore’s Cookbook, Red House Spice. The Woks of Life is particularly helpful. Created by two generations of a Chinese American family with Shanghainese and Cantonese roots, the website’s detailed ingredient glossary is a godsend when you’re lost in a grocery store, with sensible shopping advice, photos of every item, and names listed in English, Pinyin, Simplified Chinese and often several other Chinese languages too. I’ll be curious to see how their first cookbook, slated for publication in November, compares to this one. For me, these websites are not only more user-friendly – they also have a more realistic and flexible approach to how people live, cook, and eat now. That makes them more accurate – and dare I say, authentic – representations of Jiangnan culture today, which holds convenience, innovation and cosmopolitanism in high esteem along with pride in our cultural roots.

I’m sure I’ll crack open Land of Fish and Rice now and then, especially if I’m having a dinner party, but I don’t think it’ll become a go-to for everyday cooking. That’s more about my personal preferences than the book, but for me, it makes for better reading than eating.

[i] Jiangnan food is designed to be served banquet style, so I respect that it’s meaningless to give serving sizes for something like a pot of stew. But even for recipes like lion’s head meatballs, you have to read the entire recipe to find how many meatballs the recipe makes.

[ii] To be fair, there are several competing systems of romanisation for Wu, and we’d probably all fight Dunlop over which dialect she chose to represent.