Here is where I began to pack up our home.

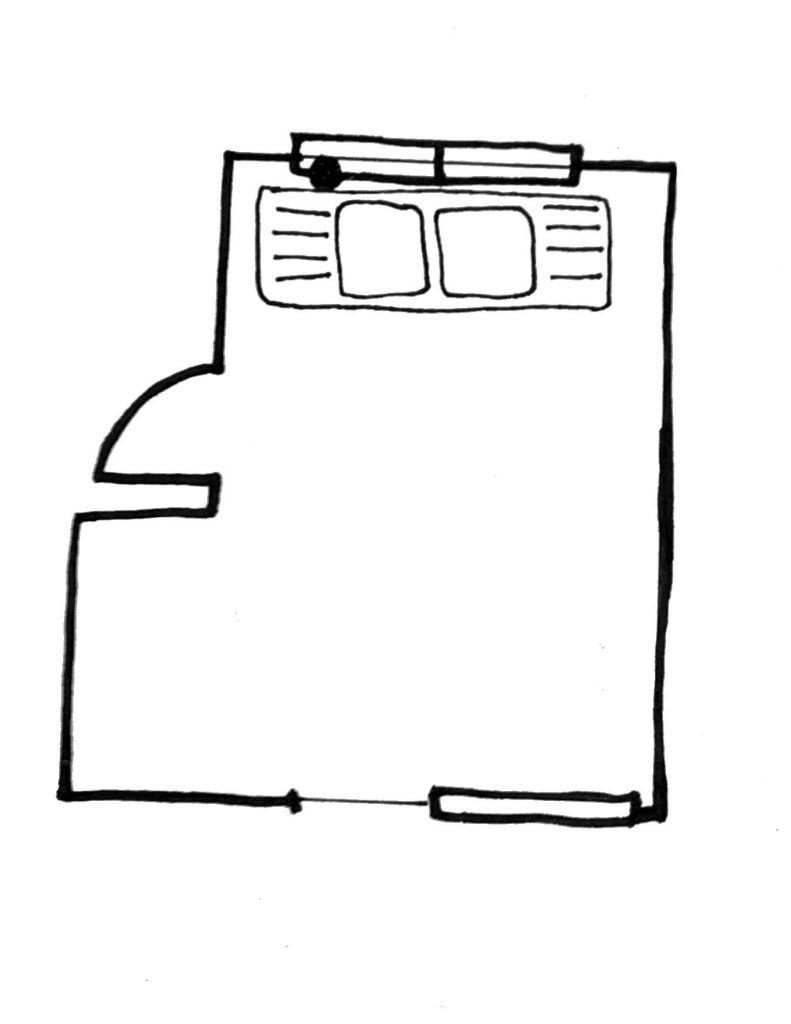

I moved from room to room, thinking about the places I had laboured. Months before, crouched on the bedroom floor, balancing on the toilet, standing against the cream walls squeezing stress balls and digging my nails into their tender foam.

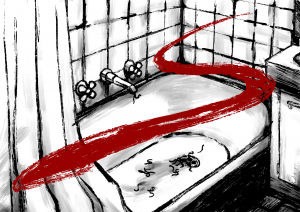

Zoe ran warm water over my back in the shower. The woman that lived in the unit before us had installed handrails. I thought about how grateful I was for them now as I lumbered from one foot to the other, slapping my palm against the wet tiles. We used to talk about her while we lay in bed at night, liking the idea that she was somehow watching over us, the three of us sharing the space like a spooky-queer version of Golden Girls.

We put plates and bowls in tolerant cardboard boxes and sealed them with packing tape. It screeched as I pulled it from the roll, protesting about being woken up to work. We emptied tightly organised cupboards, items stacked one on top of the other, everything arranged to be housed in a small space.

Here is where I saw the first sign of blood.

On the toilet paper and in the bowl. It mixed with water to create a subtle excitement in me.

In this home we spent long months together locked down, too scared to venture outdoors. I didn’t even go to the shops, too afraid to compromise the little life growing inside me. We had cloth masks arrive in the mail and dragged our tiny kitchen table into the loungeroom for each other’s birthday dinners.

Before our baby was born I manically cleaned our unit. I wanted to scrub everything: the oven; the long ignored skirting boards; the wet dust on the walls of the bathroom, growing like soft down; the flyscreen door; and the fossilised leaves trapped in the corners of the courtyard. I balanced on the brick windowsill outside the lounge room, with my tummy brushing up against the pane, trying to reach every corner of the glass. These tasks seemed imperative to our child’s survival.

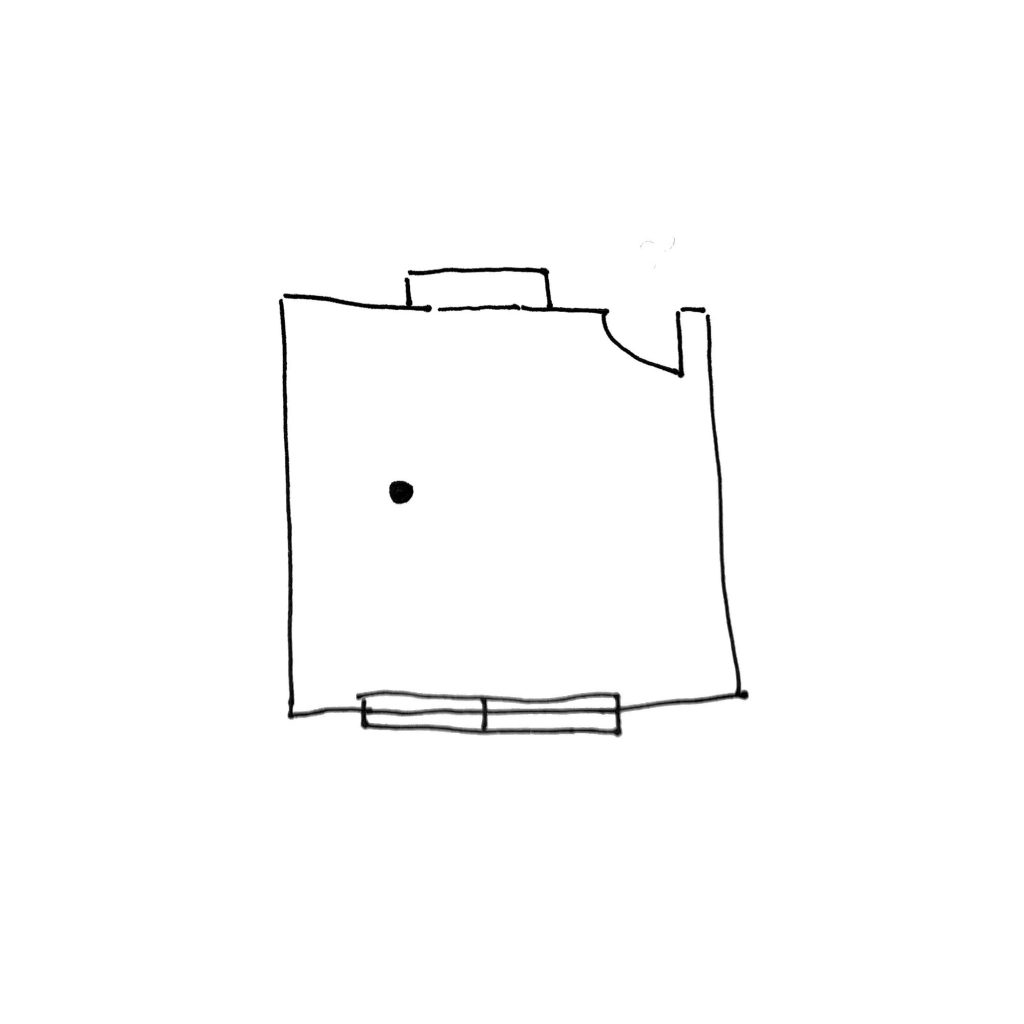

Here is the water-logged window sill where we dried the baby’s bottles.

After our baby had been taken away, a midwife entered my hospital room and told me I’d need to pump and that she’d take the milk down to him in the humidicrib. I can’t remember much, but I remember the handbag of the doctor who came to assess him: a large leather number that she fumbled around in, looking for equipment and paper to write on, like an enormous grumpy fist parading as an accessory. The bag and the humidicrib have fused in my mind – both contain fear and fragility.

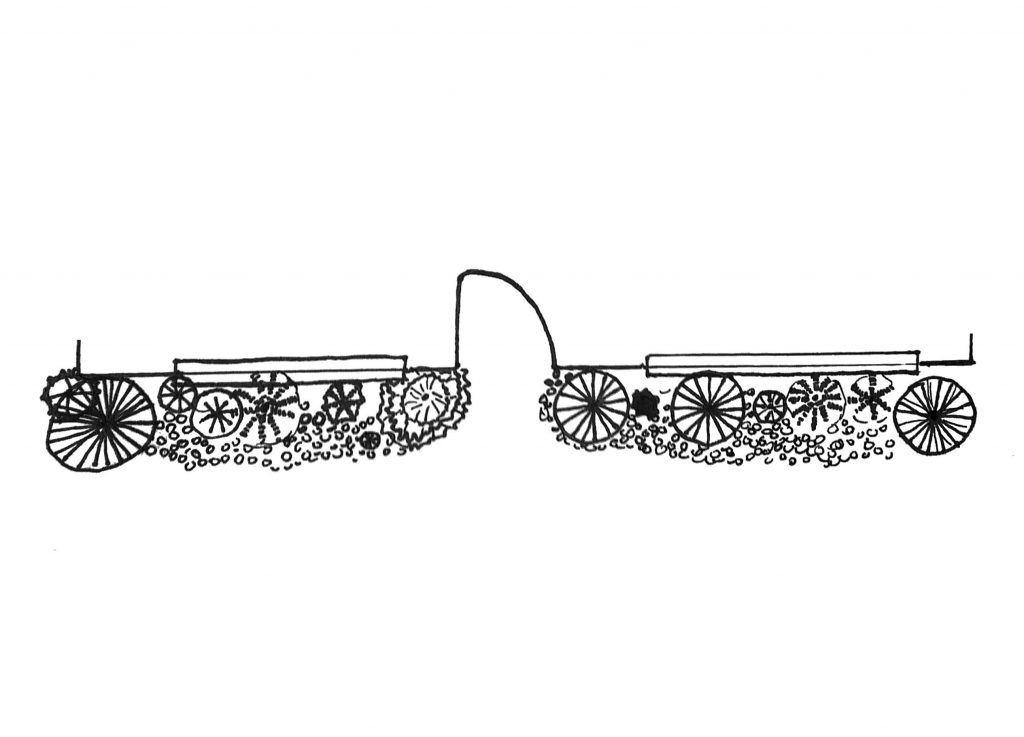

Here is where I filled the backyard with pots and raised garden beds.

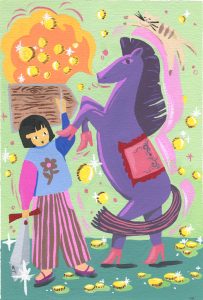

Our courtyard was almost all concrete except for a few small holes where shrubs grew and where I tipped cold coffee grounds. I don’t know how many kilograms of naïve potting mix we carted in to make a garden over the years. I planted a crepe myrtle in one of the dirt holes. It had bright pink flowers in late summer and grew so fast. I cut it back each year to thicken the spindly branches. Last summer a possum took a liking to the flowers but the branches weren’t strong enough to hold its weight. In the middle of the night we’d hear crash and thump as it fell and then scurried away along the neighbour’s fence.

Maybe it was the possum that climbed to the top of our door to sit in the glass pane one night. We sat frozen on the couch as the shadow appeared, thinking it was a paranormally tall man in a top hat coming to terrorise us.

Here is where I fell asleep breastfeeding our baby in the rocking chair.

I perched snacks and water bottles on the coffee table next to me and stuffed pillows around us. In the middle of the night the rocking motion sent us both back to sleep.

While packing, my hands became dry and cracked and the skin at the top of my thumbs peeled off. I pulled long stretchy strips up and ripped them with my teeth. After delivering the placenta estrogen levels rapidly decline, and if you breastfeed, the hormone prolactin keeps them low. Low estrogen levels go hand in hand with dry skin, low sex drive and mood swings.

Here is where Zoe and I took turns sleeping next to the baby’s cot to give one another a rest.

Curdled inside a sleeping bag, like a piece of stale fruit, my body was delicate and sour. I lay on an unforgiving cot mattress that my feet slid off the end of and was reminded of how big I was and how small the baby sleeping above me was. As I drifted in and out of light sleep, my dreams mixed with reality in a new kind of brain-nausea, the exhaustion blending with unbridled imagination. I waited desperately for the dawn.

I’ve never loved mornings more. There’s something about the warmth of the light and the noises of birds that says, ‘everything is alright’.

Here is where the globe thistle lived, and died, and lived again.

In the weeks while I was waiting to go into labour I became distraught when the neighbour’s friend accidentally weeded our front garden and pulled out a globe thistle I’d been growing. When it flowers, the plant has a beautiful steel blue, spherical flower on top of a long, thin stem. It rises high above the other plants, bold and prehistoric. The neighbour’s friend tried to tell me I was wrong, that it was a weed and should be removed. I cried for hours, thinking that it had taken seconds to remove something that had taken months to grow. I fixated on the man and his cavalier attitude. How could he not care? Being a thistle, though, it proved hardy and easily regrew after I quickly shoved it back into the dirt.

Mum came with a trailer to cart the tired dirt from the backyard out of all my pots and garden beds. Dry and matted together with dead roots, we scraped and shovelled it from the base of parched terracotta pots.

The front garden was less than a metre wide, crammed full of plants: sea holly, dichondra, salvia, a snail creeper, native shrubs, sea lavender and alyssum. Textures of blues, purples and different shades of green. I added rocks from the family farm – brown and grey, flat and sharp – hoping lizards and bugs would find them useful. It was an ordinary looking garden but to me it was beautiful. In summer, the evenings were accompanied by the sound of crickets and the front sprinkler’s spray. I lay on the couch with the dog as my tummy grew, watching the 7 pm news. The same couch where I’d lie crying after having to leave our baby in the special care nursery and come home just the two of us. The dog would come and lick my face to comfort me, standing on my tender empty stomach. The same lounge where Zoe cared for me after my back surgery and I for her after her jaw surgery. Where I lay down after having my first needle in our fertility treatment and where the midwife checked my fresh stitches after birth. Our families met our baby for the first time in this room. Sacred meetings that fill you with warm light and pass too quickly.

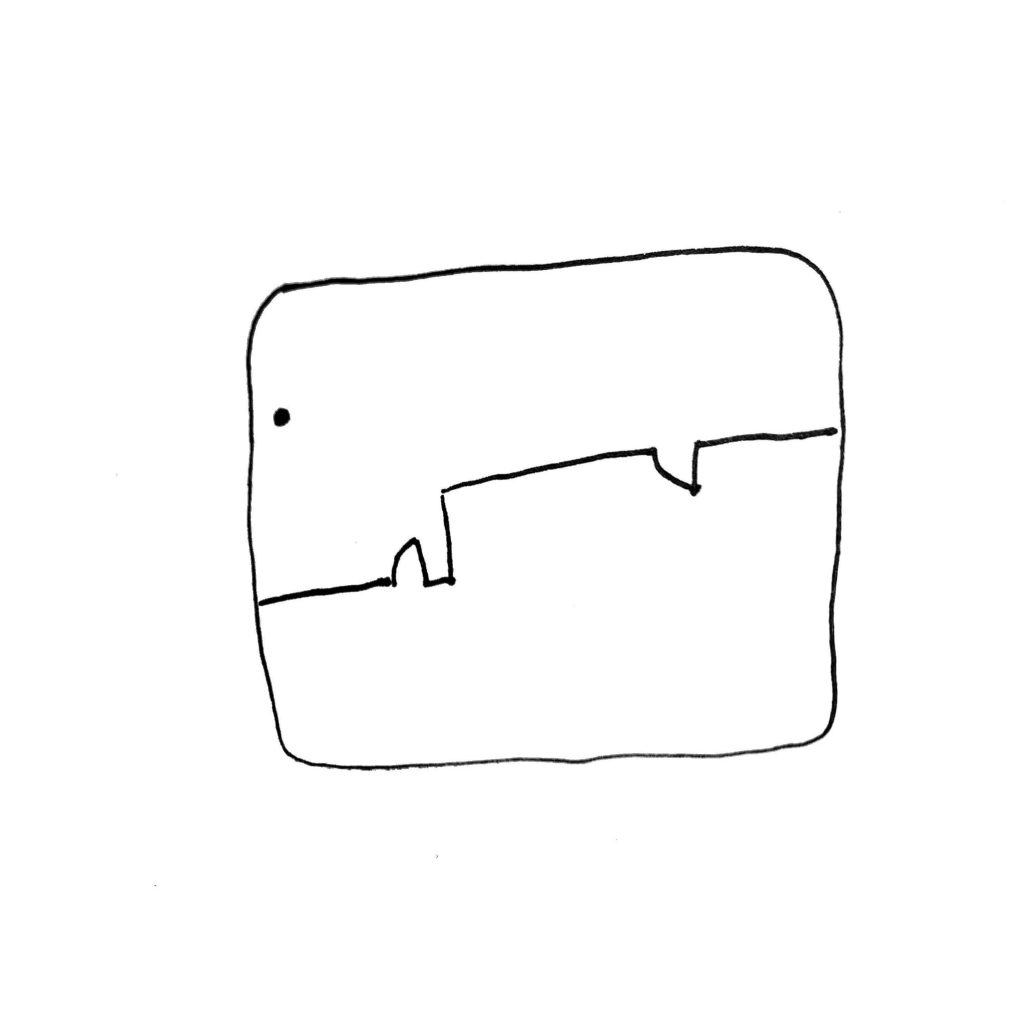

Here is the place I wanted to return to when they told me they were going to induce me.

I wanted to go home to the safety of our gentle little unit, to labour there among the daily features of our domesticity: the sagging plants, the collection of proud ceramic birds perched on a shelf, the dust, the dog, the dirty skirting boards. Thick with panic in a small hospital room we said we needed to go home and we’d be back in the morning. The hospital’s clean white room sucked up my panic, but offered nothing in return. The space was cold and stingy. I felt claustrophobic, disoriented by the bland walls. I was wearing two thick stretchy bands around my stomach to measure the baby’s vital signs, our eyes glued to the monitors.

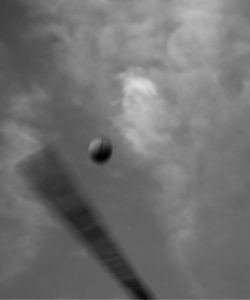

Here is where I lay on our bed punching the mattress and counting to ten, waiting for a contraction to pass.

We timed the contractions on an app on Zoe’s phone. It told us to go to the hospital but we waited longer, until they became more set in a rhythm. At least, Zoe did. I just breathed in and out and hit things to keep my mind occupied. I vaguely remember her talking to the midwife on the phone, the first of many conversations for which I wouldn’t be fully present. The pain felt different to what I expected – deeper, like stretching bones.

Here is the clothes line where we dried our baby’s clothes before he was born.

Pegging out little onesies with donkeys on them to the thick wire of the hills hoist, ready for the body of a person we were yet to meet. A body that rumbled and kicked beneath my rib cage, listening to our voices, already part of the conversation.

Here is the spot where we tipped our kitchen scraps and folded them together with dried leaves.

I gave away my compost to a friend – compost that took years for me to perfect, finally getting the right balance between wet and dry ingredients. When I dug it up there were worms in it and it looked dark and rich. I shovelled some of it into a small plastic tub for our future garden, an earthy transplant from a previous life.

Here is where we stored our packed suitcase for weeks before I went into labour.

Zoe took them from the bedroom and began to pack the car. She said goodbye to our dog and helped me into the backseat where I clung around the headrest, moaning.

Here is the first window I stood at with my baby, looking out into the courtyard at the crepe myrtle.

Like the collage from Window by Jeannie Baker, a woman stands with her baby looking out. As the years go by the baby grows and the landscape outside the window changes, becoming more developed, the natural world slipping away. This transition happened a long time ago outside our window. We hardly had a view, but there was enough to soothe our baby: the blue sky with feathery clouds stretched across it and the deep green foliage we’d planted to soak in. I talked to him about birds and plants and all the things he’ll be able to do one day. He’s the only person I’ve never been shy of. We stood there in the dark and in the sunlight alone, together, both of us as tender as upturned soil.

Georgia Mill is a writer and artist based in Melbourne, Australia. Her writing has been published by The Lifted Brow, Scum Mag, Melbourne City of Literature and Witness Performance. In 2018, she was long-listed for The Lifted Brow Prize for Experimental Non-fiction and short-listed for the Scribe Non-Fiction Prize. She is producer and host of A Fluorescent Feeling, a podcast about pain and our bodies – how we talk about them and live inside them.

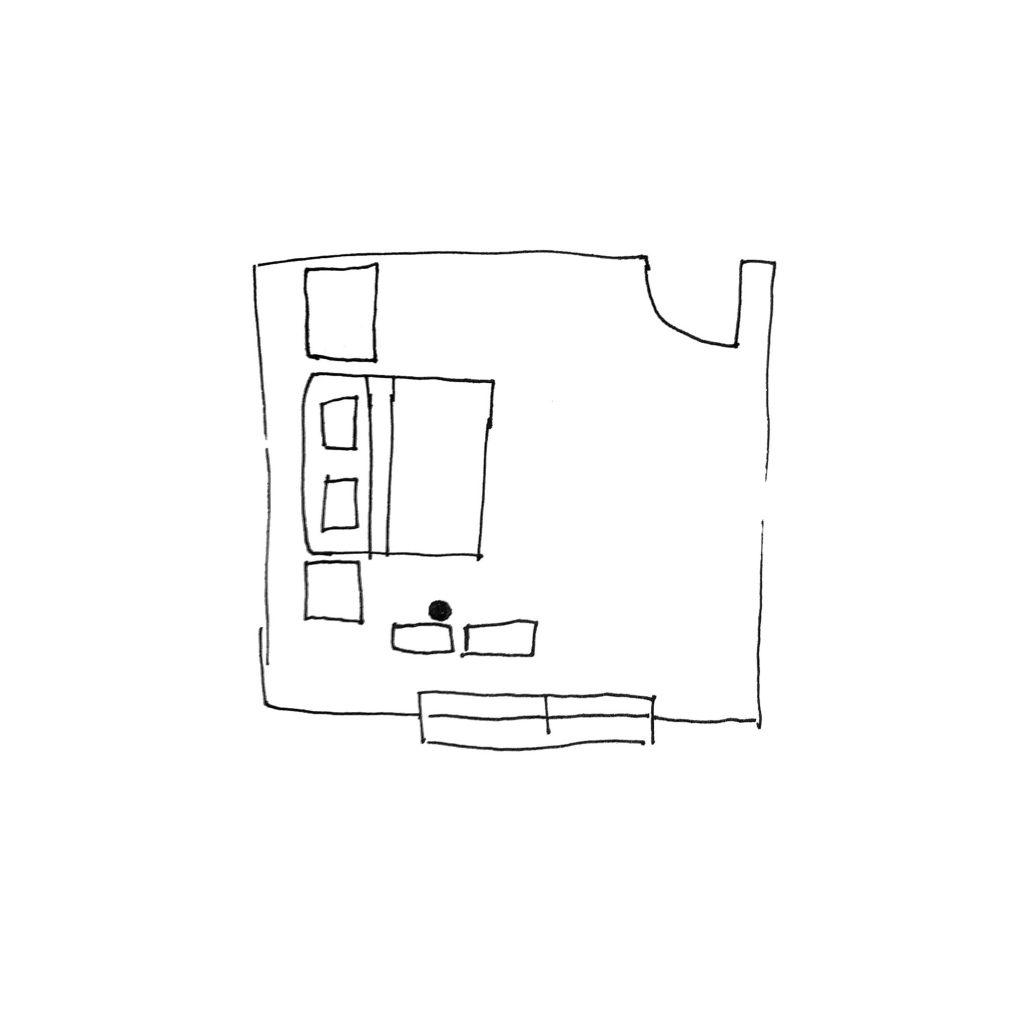

Photos and drawings by Georgia Mill.