The point is, we are now professional marketers. We are feverishly working on our Twitter personas almost as hard as we are working on what ends up on the page.

Our conceptions of how to rise to prominence as a writer usually starts with the question, “are you on Twitter?”, not “what have you written?” or “what are your ideas and what are the topics you’d like to explore?” It is first-year journalism students being told to gain exposure on Twitter to raise their profile. And as Hobbs writes, “in the way that the influencer uses her image to sell her swag, the writer leverages her life to sell her work, to editors and audiences.”

This is why Ta-Nehisi Coates’ We Were Eight Years in Power is so powerful. It shows a candid account of the life of the writer: the insecurity, unemployment checks, the financial irregularities and more importantly, the work needed to prosper. It is an answer to the snapshot glances we are fed from influencer writers: it shows the moment before and after the picture.

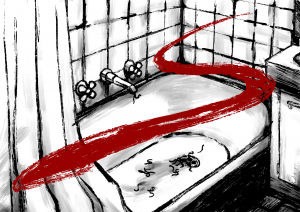

The book is made up of eight essays written during Barack Obama’s presidency, and between each essay, chronicles points of Coates’ writing career during that period. It is a book that doesn’t try to be polished or pretend the journey was easy, it does the complete opposite. It taught me what not to be as a writer. To separate the ideals of fame and inflated importance from your work. To be comfortable in the knowledge that your work may be unread. This is ultimately what I have come to believe good art and, by extension, good writing does. As Coates explains:

“Art was not an after-school special. Art was not motivational speaking. Art was not sentimental. It had no responsibility to be hopeful or optimistic or make anyone feel better about the world. It must reflect the world in all its brutality and beauty, not bring hopes of changing it but in the mean and selfish desire to not be enrolled in its lie, to not be co-opted by television dreams, to not ignore the great crimes all around us.”

On the surface, this may read as a statement of writing as a political imperative. That is true, but when I read this I also think about the lie of the writer’s public persona, the performance of what that life is: the need to mould your work on the whims of hopeful ideals, to placate the self-aware brand the writer has built.

Whether we like to admit it or not, as Hobbs writes, “…there is functionally little difference between a lauded writer with a recognizable avatar and a prominent social-media influencer. The only difference is in the way each metabolizes the experience of influence.”

And in this era of influence, we need to hold onto our work’s purpose more than ever.