Permit me, if you will, the opportunity to start my story over one more time. I haven’t been entirely truthful with you or myself.

First, a clerical error. Yes, I lost Herbert during ‘Memory’ but, no, it wasn’t Delta Goodrem. I always forget she’d left the show by that point; those sorts of details aren’t important to me. No. It was Delia Hannah.

The first time I saw her – I mean really saw her, not in glossy programme photos or in grainy iPhone footage, spied over Herbert’s shoulder as he watched, rapt, on his laptop – our palms were glued with sweat. I was drinking the house chardonnay, a dry and papery vintage; he was eating jelly babies (they were his favourite snack, one of thousands of pieces of Herbert trivia I don’t think I’ll ever forget). The wine left me in that unhappy state where you are too drunk to be tipsy, but not drunk enough to be Drunk. My interest had been in drought all show. Occasionally he would squeeze my hand, as if to say, ‘Pay attention here at least, please.’ I made a concerted effort, but I could barely stay awake.

And then there she was, a chiaroscuro painting come to life, Grizabella – Delta, no, Delia. The synthesisers tinkled; he pulled his hand away from mine, leant forward. We were in the nosebleed section, but at that moment the distance between them folded like a map. If he reached out, he could have touched her coat, its fur in topographical matts; her velveteen tights, black and sleek and shimmering, like a streetlamp’s glow reflected in a river; her made-up face, snowy, doleful, beautiful.

Apologies: I must amend the ‘when’ as well as the ‘who’. Depending on how you want to cut it, how I want to cut it – and I am recutting it – I actually lost him nearly three months beforehand.

We were still living in Adelaide at the time. Herbert wrote theatre reviews for a local rag. He loved his job, but it paid crumbs, doubly so when you consider the amount he worked: all day, hunched over in a shoebox office, salt-and-pepper hair wet with sweat, his lanky form in its ill-fitting button-up punching away at a review his editor would eviscerate, and which no one would read.

In the evening he would see new shows. Preview tickets came with a plus one; sometimes after enough bribing, begging, and cajoling he convinced me to come along. I never attended for my pleasure. Going to a critic’s preview was, in my mind, about as fun as listening to a late-era Rolling Stones album. Suffocating affairs, the audience was always a mix of Patrons of the Arts (wealthy types, humour as starched as their suits) and critics: excited, exhausted, cynical, overeager. All the ‘schmoozing and boozing’ (previews came with an open bar, an attempt to sand the edges off reviews) was intolerable. I missed many shows that halfway interested me to avoid the people who attended, so there was no way I was going to see Cats.

Those kinds of productions, Megamusicals, were never my kind of thing. I’m a graduate of VCA’s theatre program. I don’t know if the name Jerzy Grotowski means anything to you but, believe me, it should. His work was a huge influence on my one-man show, The Untold Story Inside, that I was – am – trying to fund.

My show was a chafing point between me and Herbert. We were the kind of couple that argued about everything, even during the honeymoon years. I targeted how weak-willed he could be – I had proposed; there was no way he was going to, even after eight years. He targeted my show – he was the breadwinner; I took the occasional bar job, but I could never help out as much as we needed.

We fought the night before he went to the Cats preview. Under different circumstances, that argument would have faded into the sky. Had he not gone to the show, had I said something different, had I apologised…

People – family, friends, previous therapists – have assured me a bit too quickly that it was not my fault, that relationships fall apart all the time. Everything they say is perfectly true and I don’t believe any of it.

‘It just needs a few more revisions,’ I said. Dark rings had set up shop around my eyes.

‘It just needs some real funding,’ Herbert replied.

‘We can fund it.’

‘We can-fucking-not.’

‘What would you have me do?’

‘Take more hours at the bar.’

‘But then I would have no time for my work, Herbert,’ I was trying not to sound annoyed and failing pretty badly. ‘It fucks up my sleep.’

‘Take a role as a chorus boy. I heard they’re trying to get a production of Starlight Express off the ground—’

‘I don’t think anyone wants to see a chubby gay skate around singing “Pumping Iron,” Herbert.’

‘You’re not chubby.’

I shot him a look.

‘You’re saying I should sell out?’

‘I’m saying you should self-finance.’

‘By selling out.’

‘It’s just a job—’

‘Andrew Lloyd Webber is the Tony Scott of theatre.’

‘People love Top Gun!’

‘My production is about authenticity.’

‘“Production” is a very strong word.’

Look, even though I say that argument was when I lost Herbert, I can’t really know that. It’s the truth to me, but maybe not the truth to him. If I knew when everything fell apart for him, accepting it would be easier – at least, that way, I would understand something about it all.

Herbert used to say there are two kinds of people: people who get Cats and people who do not get Cats.

The cynic in me says he just wanted an excuse to call the wedding off. Of course, I didn’t like Cats. I was never going to get Cats. He knew as much – he knew.

The optimist in me counters: that’s something someone who doesn’t get Cats would say. I have a heart that’s all right angles.

Once I heard Herbert say Cats was bad art but good entertainment. I always thought Herbert was a good writer but a bad critic. While I loved him, I couldn’t comprehend him. I was always trying to figure him out. What’s the opposite of a right angle?

In the months following the preview, Herbert changed. Nothing big at first: he took his sister, his mother, his work friends, to see Cats; he hummed ‘Memory’ while making breakfast; a bootleg recording of Delia’s performance set up shop in his ‘Watch Again’ YouTube recommendations. It was like he was moving the entire house one centimetre to the left, one piece at a time – you don’t notice anything is out of place until everything is out of place. Suddenly, he was up for hours every night working on some project. At first, I couldn’t get two words out of him about it. Then, I couldn’t get two words out of him full stop. Initially, I waited up for him… he’ll come to bed in the next minute, the next five minutes, the next ten, this hour, next hour. Surely.

One night, while Herbert was at a preview for an indie show, his editor called me:

‘Did you know I’ve been editing comparisons to Cats out of his reviews for over a month now?’

‘I don’t read them.’

‘I edit them out.’

‘I mean I don’t read his reviews.’

A short discussion of Cats followed: did I understand his obsession? No, how could I. I didn’t understand Cats – its emotions, plastic-wrapped, breathlessly determined to prove itself in some way connected to the human experience, in so doing only revealing its total disconnect – full stop.

‘Take “Memory” for example,’ I said. ‘Doesn’t it feel like a four-chord song filtered through Google translate a couple of times?’

His editor, who had stopped listening some time ago, changed the subject. ‘He’s determined to interview her, you know.’

‘Interview who?’

‘Delia, of course.’

His editor described his behaviour as fanatical. Delia, despite working as an actor, is quite a private person, but Herbert was sure he could be the one to interview her. He pestered the production, every day.

‘This is very hard to swallow.’

‘Swallow it,’ his editor said. ‘I’ve asked him to stop but he won’t. Either you fix this or he’s not going to have a job for much longer.’

They hung up.

‘You’ve been burning the candle at both ends recently, maybe you should take a break?’

‘I don’t want to take a break.’

‘Let’s go to Perth for a weekend.’

‘We could go see Cats while we’re there?’

‘I’m not going to see Cats.’

When I finally agreed to go see Cats, it was out of a morbid sense of curiosity. The trip had felt doomed from the outset, a deep black rot in its foundations. Herbert was listless. He wore a far-off expression, all smudged at the edges. If I hadn’t dragged him out of bed and around town every day, I doubt he would’ve moved at all, his washed-out appearance – watered-down milk – blending with the white hotel sheets.

I didn’t think my going to see Cats could repair the rift that had grown between us. On some instinctive level, I knew there was nothing to be done. I just wanted to know who had been keeping his side of the bed cold for the past few months.

We didn’t break things off immediately – that happened a few weeks after we got back from Perth – but it might as well have happened during the show, during ‘Memory’. Everything that followed Herbert pulling his sweaty hand away from mine and leaning forward, toward Delia, felt like a foregone conclusion.

I’ve tried to recall details about those following weeks but most of it feels smoke-screened. We floated through the house (already it had stopped feeling like ‘our’ house) as ghosts. I know we spoke, often for hours at a time, but never about anything important. I know we didn’t argue, not once.

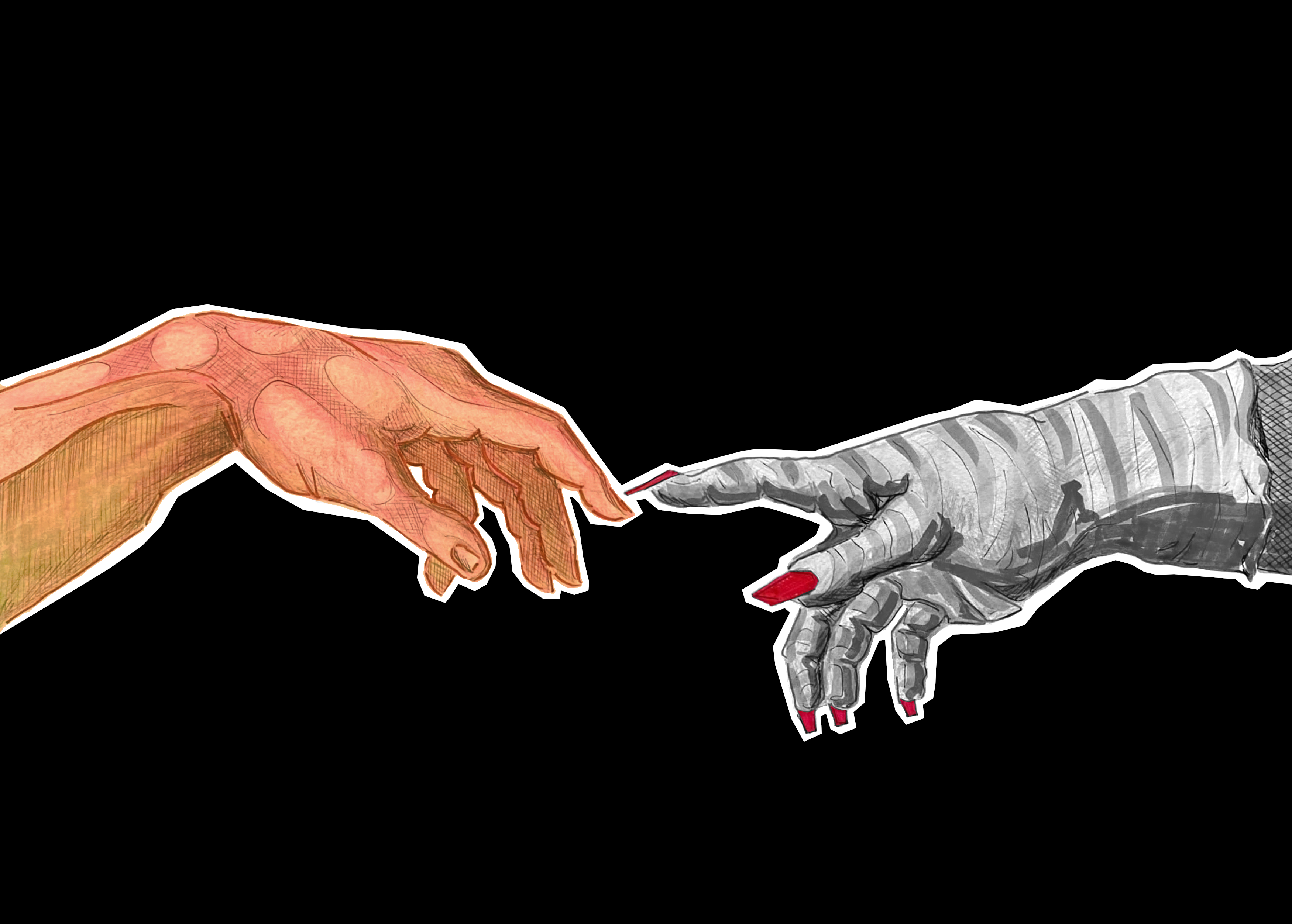

Even the night Herbert left for good feels like someone else’s memory. Boxes stacked precariously in the back of the car, which he reversed down the driveway, red taillights all but consumed by the gentle warmth of the streetlamp, he shot me a smile, crooked as the crescent moon. As he turned into the street and began to drive away, I reached out, maybe to wave or maybe in some forlorn attempt to catch him. I can’t say for sure.

In truth, I still feel like I’m at the closing night of Cats at the Crown Theatre. Every memory of Herbert and me, every moment that has followed, pleats back into that one. Time and place stand still when I close my eyes: she’s there – Grizabella, Delia – singing ‘Memory’, her silk-ribbon voice skitting across the key changes, over the climax, somehow selling the song’s melodrama, its unreality, with ardour. He’s there, Herbert, reaching out to her, his expression exploding with a firework intensity – Archimedes in the bath – as a tangled knot of emotion unravels, pulled into a clean string. And I’m there, far away in the seat next to him, wishing I could compress everything between us, our dialogues and history, our meaningless arguments, all those lead emotions, into nothing so that I – a furline shadow hesitating toward the light of a half-cracked door – might reach out and touch him.

Joshua Sorensen is an editor at Flip Screen and a student at UOW. His fiction and criticism have appeared in Kill Your Darlings, Overland, Archer Magazine, and Jumpcut Online among others. Movies starring Holly Hunter are to him what lamps are to David Byrne. You can follow him on Twitter @namebrandjosh

Art by Sophie Tegan Gardiner. Sophie is a writer and Angelina Jolie devotee originally from Aotearoa. Their work has previously been published in Going Down Swinging, Starling, Voiceworks and the Bowen Street Press Review among others, and online at Meanjin. They started as editorial intern at GDS in 2021, and are currently working on their debut novel: a horny, queer coming-of-age set on a cruise ship.