It was a year after the dogs were meant to shut down: Thursday, early evening, the road mostly bare. It wasn’t a trip we made often. We didn’t feel the disdain I think we were supposed to – a detached interest, I guess. If we’d lived a few suburbs closer, Cringila, or anywhere past Port, maybe we’d have come more often. There could have been a version of me that the bar staff recognised. One who knew a winner just by looking at her.

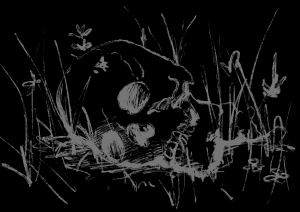

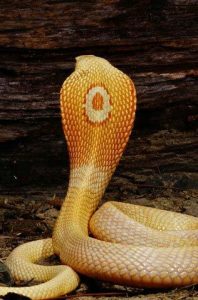

We were heading for the Dapto track – not the circuit to the north, famous for night markets and folk festivals. Down south, where the greyhounds were lean, dark blades of muscle; ankles webbed like batwings; veins wrapped like strangler fig up their legs. It’s one mindless highway all the way down, twenty minutes past horses out to pasture and half-finished housing estates.

It was my first time back since I’d left, and I felt some deep, untempered desire within me. I stared hungrily at the carelessly fenced fields; the rusting shell of a hatchback abandoned on the verge. I wanted dirt. I felt a sharp, almost spiteful happiness when Dad suggested the track. Maybe spiteful isn’t the right word. But happiness with teeth. Happiness, as in I understand this world and other people don’t. Even now when I catch a line of grime under my fingernail or a patch of burrs on the arm of my coat, I feel it.

Mum drove while Dad nursed a beer in the passenger seat. JJ had earphones in and wasn’t in the mood. We passed trucks loaded with coal, wood, fuel. When we reached the exit, Dad put one hand on the headrest of Mum’s seat and guided her onto the overpass, through the unlit streets. A man hosed down his yard in the growing dark. The track wasn’t far from the highway; the only thing separating it from the procession of northbound traffic was an unlined carpark and a vein of pine trees a few trunks deep.

To get to the stands, you had to walk past the doghouse. The building was all concrete, so the yapping of the dogs bounced in on itself, bright in the clinical white lights. A few dogs were dressed, standing silently in the adjacent yard. JJ pressed himself to the fence and stared at them. A tawny one wearing emerald green brushed past him; a pink-coated dog with charcoal fur stared into the middle distance, her owner rubbing her down.

All the greyhounds I see now are retired, but I remember those animals, so uncertain without the chase, like an actress pulled offstage mid-monologue. Ease was foreign to them, their eyes still alight, their heads bobbing up and down with each step.

We hadn’t been to the dogs in years. Last time we went I was maybe thirteen, fourteen. JJ was six. Now, he was old enough to show concern; he frowned at the dogs, eyes tracking the owners as they chatted, laughed. The floodlights beaming onto the track cast both the yard and the carpark in a pale, second-hand light. This would be our last visit. I didn’t know it then.

‘Isn’t this illegal?’ JJ asked suspiciously, looking over his shoulder at Dad.

Dad had stopped behind us to peer into the yard. He waved his beer vaguely, his other hand between Mum’s shoulder blades. I glanced at JJ’s furrowed brow, then back to the dogs. I’d expected them to look sad, but they didn’t have any discernible human emotion on their face. You know, they’re animals. They looked up at us with their big, wet eyes, then they looked away again. One was enjoying some attention from his owner, nosing his elegant snout into her palm. A few of them lapped at a bowl of water.

Our parents had moved on, walking away towards the yellow light of the squat, rectangular building where you could place bets, buy drinks, watch the trotters in the interval between dog races.

I touched JJ’s shoulder. ‘Come on. They’ve got food and stuff inside.’

‘No way.’ He turned his incredulous gaze on me. ‘I’m not going in there. What the hell are we doing here? Since when do we watch this stuff?’

Sure, it had been a while, but I found it hard to believe he’d forgotten us visiting as kids, vying for the dogs’ attention, helping Dad place his bets. He’d always let JJ choose the dogs, based solely on their names, and lost money every time. Dad probably would’ve won something if he did it himself, but he never wanted to. He’d sit on the stairs of the concrete amphitheatre with JJ on his knee, helping him mark out box trifectas with those tiny pencils they use for elections. Mum hovered over them, cheering regardless of who won. She didn’t want any of the dogs to feel bad.

I moved off and began wandering after our parents, leaving JJ to skulk around the cages and do his pre-teen moping thing. Someone opened the door to the bar. Through it, I saw my parents’ backs, their arms pressed against one another as they walked toward the desk where winnings were collected. A body blocked my view, moving past me through the door with a small plastic bag of party mix. I looked up. When I met her eyes, all sound dimmed. A shard of yellow light fell over her shoulder, scattering onto the asphalt between us. Her gaze darkened familiarly; that incredulous fury she used as a guard. It was too late to pretend we hadn’t seen each other.

We stopped, both blocking the doorway. A broad man in an RSL cap and a waterproof jacket lumbered past us, grumbling. She ducked out of his way, stepping closer to me, then thought better of it and moved off to the side instead. She was still trying to open her lollies, slowly, like she was in the back of a classroom, about to sneak me one under the table.

‘Are you back long?’ A tight, irritated question, bypassing small talk. Her face turned down and away from me. She’d finally made a hole through the plastic.

‘Just for the break. Three weeks. Ish.’

She raised her eyebrows at that, gaze still on her hands. When she looked back up at me, she tilted her head a little, as if we were both in on some kind of joke. Or not that. More like she just didn’t believe me.

‘You should’ve said.’

Yeah, right. ‘I should’ve said?’

She laughed, fishing a snake out of her bag and biting its head off. ‘You gonna come sit?’

‘Really?’

She shrugged. Chewed. Swallowed.

We sat on the cool stairs of the stands. Mum and Dad were still inside, probably placing bets, ordering drinks, striking up conversation with strangers. Stuff like that was easy there. People were always ready to talk: about their dogs, the injuries, the winnings. The two of us, meanwhile, endured silence. She tried to distract herself by pulling a bag of tobacco out of her pocket, balancing it on her knees. Everyone smoked there, the air always carrying the scent of it, little orange pinpricks floating in groups of three or four in the dark. Kids dangled from the railings at the bottom of the tiered seating, doing front flips over the bars and hanging from their knees, hair long and trailing on the ground, wearing hand-me-downs. Last time I’d been there I was dressed in my cousin’s clothes, a cousin older than me and smaller too, but I was the youngest girl and the clothes had nowhere else to go.

She dug through the bag for another snake, curled at the bottom beneath strawberry creams and jelly babies. I watched her long fingers. ‘You here with your brother?’ I asked.

She pulled the snake out, pinching it at either side and stretching it taut. ‘Can’t believe I told you about that. But yeah. He’s got a dog in tonight.’

‘Why?’

‘Cause he races dogs?’

‘No – why can’t you believe you told me that?’

She wrapped the snake around her finger. It wasn’t an animal anymore, just a strip of sugar, dye, and gelatine. ‘It’s embarrassing.’

‘We used to tell each other all kinds of embarrassing stuff.’

‘Didn’t keep you here.’

Her darting eyes: her hands, the track, my face, her hands. The next lot of dogs were being led over to the boxes on the far side of the track. A little boy in front of us held his iPad up, hoping to photograph the moment they crossed the finish line.

She blinked hard and stared, resolutely, at the track.

I could understand her embarrassment. This wasn’t a normal world, the long, snapping legs racing after that blur of tradie-orange; the owners on their knees in the loam, wrestling the dogs out of their borrowed jackets; moths drowning in the abandoned schooners on benches; the children practicing gymnastics on the concrete.

‘You like it there?’ she asked. ‘Like it better?’

Not too far from us, the highway: trucks and commuters flashing by billboards for life insurance and the McDonalds at the next exit. I could hear the oceanic rhythm of the cars as they pulled close and then pushed off, away. Every so often an engine snarled loud above the rest, someone hooning up into the city centre, whooping out the window.

‘Yeah,’ I replied. ‘Heaps.’

Her eyes had moved on before I started speaking, and now she smiled, finally, in distant amusement. Something more interesting was happening over my shoulder.

I don’t know how JJ did it. I’ve considered a few theories since: were the locks electric, so he could cut the power and let each door swing open automatically? How would he have gotten access to the power in the first place? Then again, it feels equally as impossible for him to have walked through and opened the doors one by one without being spotted. He still hasn’t told me. Whatever happened, there was sudden shouting, swearing, everyone running down out of the amphitheatre, lining the track, some legging it towards the enclosures. The dogs were out.

I assumed the worst, the highway – gory, prophesied flashes of their delicate ribcages beneath SUV wheels, their velvety ears pin-cushioned by glass, a flood of dogs across the road silhouetted by truck headlights, and then a swift silence. Black-red tyre tracks tarring the road into the city. That didn’t happen. They didn’t run towards their owners, who chased after them and yelled desperately, the kind of noise that punches up and out of your chest unconsciously. They didn’t run to my brother, who thought himself their saviour. They didn’t run to the yellow light of the bar, where they could sneak their thin noses into bags of sweets; or watch other animals run other races on other courses, in other cities, in other countries.

The dogs ran for the track. They burst through the gates they were normally led through on leashes, and when people tried to block their way they leapt up and over the fence.

Soon enough, everyone realised the greyhounds couldn’t be caught. They crowded the track and watched as the dogs ran in laps. They weren’t chasing anything. Without human noise, the sound of their thundering feet spiralled into the air uninterrupted. They didn’t run one lap, or two. The pen didn’t swing out to catch them, to corral them into a buzzing, snapping huddle. They took long strides, spending half-seconds suspended in the air, their taut muscles rippling beneath the lights.

I searched for my brother. He was standing back from the crowd, arms limp at his sides, expressionless eyes on the dogs. I could lie here, say I thought of going over to him, but all I did was turn my gaze back to her.

The soft, pink tip of her tongue was pressed against a freshly rolled dart, sealing it. She held it between her lips, lifted a lighter to the end of it. Through an exhale of smoke, she watched the dogs, blurs of black and brown and grey. Someone nearby asked nobody, asked the air, when the hell those dogs were gonna stop, because they had to stop, right? The smoke in her face wound upwards and away as she leant her elbows on her knees and met my eyes. She was still. There was an ease in her that was new to me. I realised, then, that nothing in the world would ever surprise her.