OVERTURE // WOMEN HOLD UP HALF THE SKY (a Vietnamese proverb)

*

A FEDERATION BUILDING ON GADIGAL LAND

An art gallery, terracotta and sandstone. In the background, the skyline, the harbour, the bridge, the city of Sydney.

(BUSHFIRE – MORNING)

REINA is waiting under the brick archway of the art gallery. The green doors are locked. REINA doesn’t have a key.

LUCIA is trying to send a text message as she runs out of the nearby train station. She has the key.

LIGHT RAIL grinds steel against steel, crawling down tram tracks on Hay Street. HORNS blare from the joined lips of Pitt Street and George. BUSES groan away from the transit. THE CITY scores its own libretto. LUCIA crosses the road to meet REINA, adagio.

A beat. LUCIA and REINA turn to us, and ask:

How can performing bodies be archives of past traumas, sites of reclamation, sites of collective and reconstructed histories? What happens when we laugh into the void historically carved from our bodies? What happens when we fill those gaps up with food, time, and love? What happens when these performing bodies join arms not in battle, but in friendship?

ACT 1: THE SIGNS

Harmony

Maturity and drive

Mutual attraction

In flux

Spiritual awakening or denial of reality

Challenges

Poor communication

Jealousy or judgement

Power struggles or hopelessness

ACT 1, SCENE 1: FIRST MEETING

The first text I ever sent REINA was to apologise for running late to the art gallery. We’d not yet met, so I signed off my message with, ‘Sorry, this is a terribly tardy first impression’.

I ran from Central Station to meet her in November – during the Black Summer – as bushfire smoke moves into the city and curls everything up in its orange hearth.

Sounds of laughter,

And radical joy bubbling from the heart of a city

We never belonged to…

All I know about REINA is that she’s newly employed as a curator at the gallery, and that she’s a dancer who has moved down from Queensland. I know nothing about dance, but I know a thing or two about performing. I spend a lot of evenings in rooftop bars and quiet cars that summer, sitting under a moon burnished orange from drifting ash.

I dream of ancestors’ bones held

Inside the belly of a sound,

Echoes of the remains of the hearth.

With the brutal weight of gravity bearing down.

We are now the sound…

*

Set designs of Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schӧnberg’s Miss Saigon often frame the sky in flame. It smolders with the beauty of a theatrical sunset – even if beneath it is a country enduring US General Curtis LeMay’s declaration to “bomb them back into the Stone Age”. A young Vietnamese woman walks into the bar. Her employers call her ‘Princess’, though the only authority conferred upon her is metaphorical. She orbits like a satellite around a system of labour that fails to care for her, only harnessing her name as a signal for her to return to work. This is where Kim’s fetishisation begins, as a body valued only by price, not name.

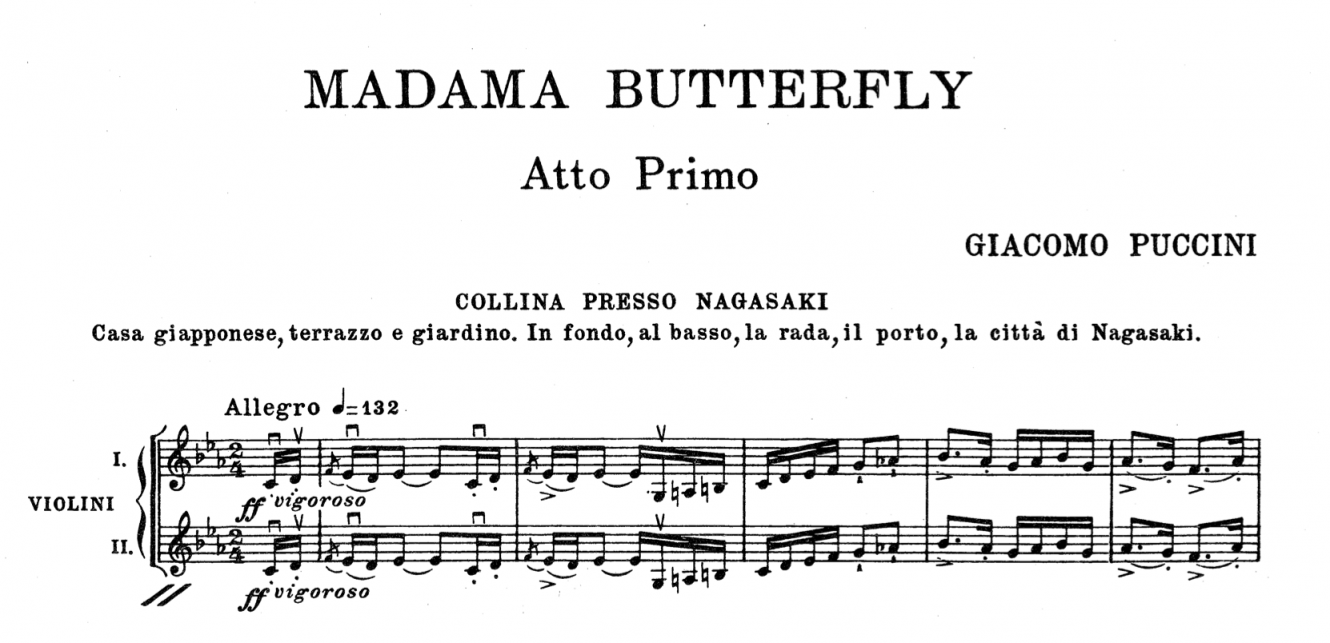

Likewise, an early documented instance of Asian fetishisation can be found in Madame Chrysanthème, a thinly fictionalised account of a French naval officer’s time visiting 19th century Japan. Madame Chrysanthème went on to be wildly popular when it was published, and marks the genesis of the Oriental prose genre.

Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is one of the most popular opera productions performed by Australia’s four major opera companies. These companies have had so many revivals of this production that most opera buffs have likely seen it several times during their lifetimes.

The findings of the National Opera Review and Discussion Paper suggest that these companies need to stage popular productions like Madama Butterfly to survive financially. Opera Australia has evolved and moved with the times in recent years too, occasionally casting talented Japanese and other Asian Australian sopranos for the part of Cio-Cio San. In typical Orientalist tradition, though, a European soprano is cast in the role, creating “exoticised nostalgia in the name of authenticity”.1 Victoria Pham, “Opera Australia and the Expense of Orientalist Spectacle”, Decolonial Hacker, August 23, 2021, https://www.decolonialhacker.org/article/opera-australia-and-the-expense-of-orientalist-spectacle.

*

The Wikipedia entry on Miss Saigon describes it as “a coming-of-age stage musical… based on Giacomo Puccini’s 1904 opera Madama Butterfly, and similarly tells the tragic tale of a doomed romance involving an Asian woman abandoned by her American lover”. Grieving a doomed romance is hard enough with a friend listening along, let alone during the overtaking of a city, or the apotheosis of an ideological war.

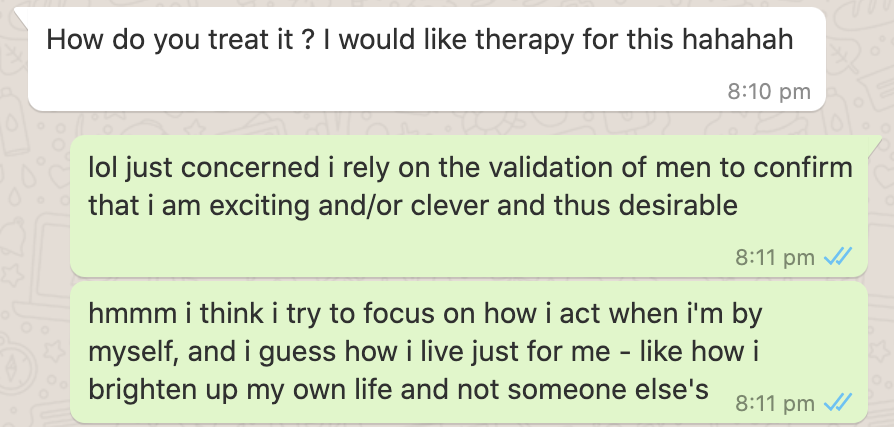

My friendship with REINA began one lazy afternoon in the gallery, when we suddenly began sharing stories of our own doomed romances during the pandemic – stories which began in jest, but inevitably descended into resignation and disappointment, as it goes. I’m fairly certain I began with a joke about loneliness.

Despite being crowned ‘Miss Saigon’ after marrying an American soldier, promising a ticket out of the country, the brothel worker Kim labours on and survives alone until her life is exchanged for her child. Her worth is only determined through her body being bound to contracts and transactions; marriage, itself, is a contract. The only confirmation of Kim’s value as a person is extended by a purportedly righteous man of war – as her to-be husband, American GI Chris proclaims, “she is no whore / you saw her too / she’s really more”. It’s a grievously dualistic Madonna/whore assessment of a working woman’s character, but I would not have expected a detailed critique to be delivered in a Broadway ditty anyway.

*

In American history, 19th century Asian immigrant prostitutes became commodities that were brought back from the tourist gift shop of war and supposedly enticed the young, White soldiers away from their duties. The Asian body remains a site where colonisation continues to be promoted, gifted as remuneration.2 Elise Song, Asian American Sex Workers Book Club (Teachers College: Columbia University, 2021).

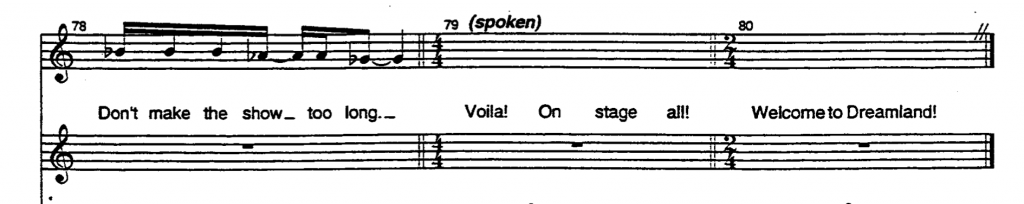

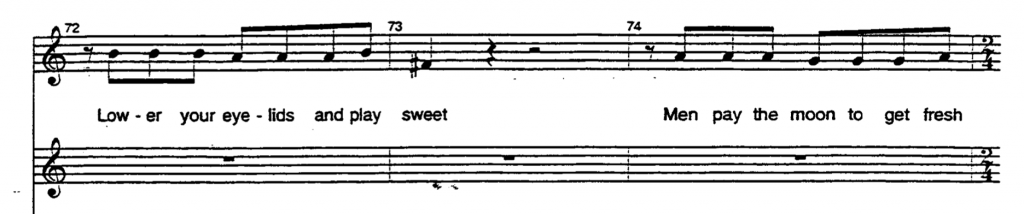

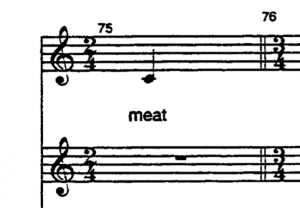

It’s a terrain well-trodden, the same magic trick executed over and over again – a voila! proclaimed to deaf ears. If this subject is so played, then let us have our fun. Let us take these men to the chopping block.

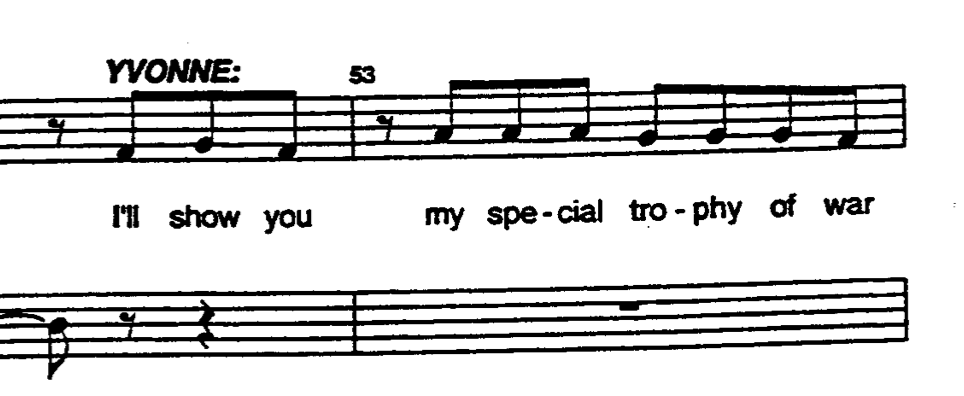

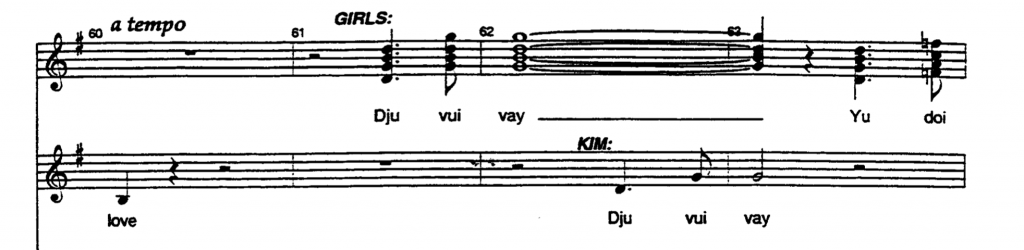

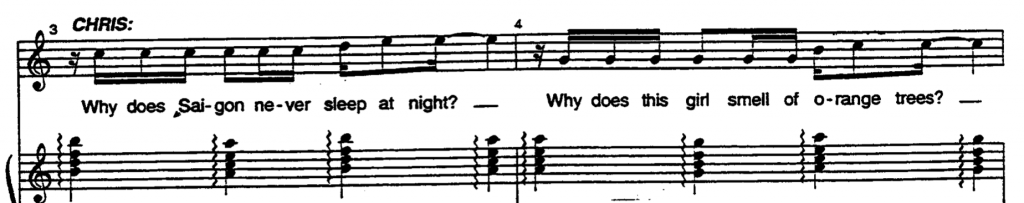

I open a scanned copy of the Broadway musical and begin dismembering, quartering time signatures and music bars like REINA and I slice orange quarters to share in summer. A friend of ours texts me, ‘You know, in Spanish, another word for “soulmate” is “your half orange”’. When we slice things, we share them.

I rearrange the sheet music. I pass it to REINA. Together, we listen for the voices of other women speaking. One of the voices is my mother, asking if I’d like some fruit. She’s sliced up some grapefruit, some orange, some watermelon, and plated it in a sweet composition. The fruit sings, and I reach out for its parts. I recompose the body of a Vietnamese woman shot – shot through with a bullet that a French man wrote into her hand, shot through a camera lens as she sees her crying daughter off at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in 1975, while Sài Gòn falls. This is the photograph that French lyricist Alain Boublil cites as his inspiration for Miss Saigon.

The Vietnam War era is synonymous with an expansion of the boundaries of Western journalism, with ‘Pulitzer Prize-winning’ prefixed to many recognisable images of this theatre of war, as shot by American photographers. White stewardship over popular representations of Vietnamese history has provoked an outpouring of narratives of victimhood and survival from writers of Vietnamese diaspora. However, playing the victim also wields its own power and capital.3Barbara Johnson, “Muteness Envy”, in The Barbara Johnson Reader (New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020), 200-216. Postcolonial cultural theorist Graham Huggan observes that “writers and thinkers have recognised their own complicity with exotic aesthetics while choosing to manipulate conventions of the exotic to their own ends”.4 Graham Huggan, The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins (New York: Routledge, 2001), 32.

But: must pain act as creative currency? So much of the canon of Vietnamese stories is encoded with our families’ firsthand accounts of violence, fear and pain; the same terrors that galvanised a mass migration in the first place are suspended in the imagined worlds of our art and literature. My mother, whose own coming-of-age was swept up in the turbulent climate of 1970s Sài Gòn, still reminds me to enjoy my youth. Maybe I should heed her words in the stories I write in my own coming-of-age too. At times, works by artists of the Vietnamese diaspora illustrate Huggan’s argument, executing a “simultaneous erasure and exacerbation of cultural difference under globalisation” to attract the sympathetic white gaze of editors, curators and panel judges who hold the keys to spaces where these Vietnamese artists can accrue cultural capital, air time or a spotlight.5Paul Giffard-Foret, “Southeast Asian Australian Women’s Fiction and the Globalization of ‘Magic’”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 50, no. 6 (2014): 687. But we’d rather not close the curtain on our joy.

ACT 2: THE NIGHTMARE

| Relations and friends [looking pityingly at Butterfly]

| I think her beauty

| on the wane,

| ’tis on the wane.

\ He’ll never stay.

ACT 2, SCENE 1: MADAMA BUTTERFLY

Can you even comprehend what it is to embody a nation’s history

through dance?

Beauty and elegance

How could you ever understand?

I imagine my body as a vessel of all that has preceded it

The rapes, the violence

Wearing a messy black wig

My body is lowered onto the stage

Entangled

Feeling the ropes of blood intertwine

Vessels to a womb

I am held

And carried

Dark hair entwined with rope

I imagine my small, waif-like body,

becoming your nimble power fantasy,

pervading the mind,

tainting it

with love and despair.

The sheer elegance denies and traps

the tapestry of histories that I inhabit

in this ceremony,

this ritual,

this opera.

間 gap

I imagine this, I dream this. An account of a performance that never should have happened. This dance was performed by a body that was not mine, a body that does not know the reality of living in a vessel that will always be hyper-sexualised, seemingly submissive and vulnerable in the eyes of many.

間 space

The scene for the imagining is taken from Opera Australia’s Madama Butterfly (2019). The stage design, suggestive of a cave, displays the skills of Japanese bondage ropes tended by robotic androids. The production’s dominating images are a sensory overload, sumptuously decorating Giacomo Puccini’s operatic score – deep red ropes in a butterfly shape, in which a white Australian female dancer, doppelgänger of Cio-Cio San (aka Madame Butterfly), is suspended Christ-like above the stage before being sold off. Moments of love and despair. Moments of re-enactment of what it means to live in this body, to pretend to be ‘Japanese’, to be of the Orient.

夢 dream

This butterfly effect continues to haunt me. I have dreams about being a mutilated woman, cut into parts, unidentifiable, unknowable. I wonder, if I were the one performing this dance, how would I feel about reenacting this story? Would I become its victim, subject to the grand narrative of a ruined woman, ‘saved’ by a White man, strung up and restrained? Would I feel as liberated as I am restrained and objectified?

ステレオタイプ stereotypes

I’ve seen various versions of this work over the course of my short life and the feeling is always the same. I remember my Anglo-Australian grandmother telling me that I should see Madama Butterfly. I was impressionable and young, and amidst ballet training that was almost entirely white. Seeing the inclusion of a Japanese ballerina in the principal role in the Australian Ballet meant something to me. I was inspired.

However, when I reflect upon seeing the work now, I question why one of the first performances I saw with an Asian woman in the ‘principal’ role disempowered her as much as it heralded her as the madama protagonist. A war of attrition, taking strength from an already disempowered body, the sexual tale of a victim of patriarchal colonialism told again and again for the consumption of Western audiences.

物語 stories

The stereotype of the Asian woman as simultaneously hyper-sexualised and submissive is borne of centuries of Western imperialism. How can these archaic storylines persist and continue to perpetuate stereotypes about East and Southeast Asian women and their relationships with Western men? Why do we need to perpetuate this spectacle? It merely celebrates and beautifies the suffering of this fictitious woman who was the result of European and American imaginings, and plays into the structural oppression already faced by women in their societies. We are not commodities. Why does waiting for a disempowering, one-sided love and its ultimate betrayal bring enjoyment to so many?

Stories that demonstrate pain, pleasure and power have seeped into my consciousness. I’m still discovering what it means to love and be truly loved in return, to be vulnerable at the hands of a male partner as I grapple with the fear of being objectified. Depictions far worse than an illusory floating Madame Butterfly proliferate in the dark corners of online cesspits.

ACT 2, SCENE 2: PARRY AND FIRE

“Can I take a picture of you?”

REINA snaps a photo of me in my fluorescent yellow mouthguard one afternoon at the art gallery, as I’m hauling my gym bag onto my shoulder to leave for fight training. Our 4A team has moved to a temporary gallery for the year: a narrow glass-fronted space with a white curtain that dramatically tumbles from the ceiling to the floor, forming a doorway to separate the street-facing exhibition space from our makeshift offices out back. Sometimes I might deflect a gallery visitor’s question by saying, ‘I can ask the curator’, upon which REINA and I would begin frantically ruffling for an opening in the huge swathes of curtain fabric, so that she could emerge to answer.

REINA jokes that we work in a bathhouse. Maybe like the humongous baby Bō who inhabits the bathhouse workplace in Spirited Away, this curtain is some absurd magnified version of noren (暖簾), the signature fabric dividers that punctuate much of Japanese interior design.

And so, I migrate from The Bathhouse to the sweaty sauna of the boxing gym.

Before light sparring, we start with catch-and-return partner drills: parry the jab and fire a cross over your opponent’s arm. Aim for their face. My reaction time is slower than I’d like, and being continuously punched in the face will either force a boxer to tighten their guard or flinch even more noticeably as they anticipate being hit.

In such a primal combat sport as boxing, body language and breath are a fighter’s means of performance and expression. Boxers hiss and grunt to maintain timing, focus and endurance while throwing combinations. The acoustics of hitting flesh (or bone) and taking breath fall into a syntax for those conversant in the language of boxing. Likewise, any mildly literate Vietnamese speaker would register the clamour made on stage by Vietnamese characters in Miss Saigon as merely noise. At best, it is noise with a faint echo (if you really strain to listen) of words such as “happiness” and “love” in Vietnamese.

The West’s abject fascination and disgust with the East and Southeast Asian woman generates an economy of power: “a division of labour into those who rule and those who supply them with magic”.6Wendy B. Faris as cited in Paul Giffard-Foret, “Southeast Asian Australian Women’s Fiction and the Globalization of ‘Magic’”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing 50, no. 6 (2014): 676. An allegorical depiction of this dichotomy would be the American GIs entering the brothel to be supplied with magic by a slew of Vietnamese bar girls vying for the chimerical crown of ‘Miss Saigon’. Confusion of truth and artifice is also what undergirds the distrust and suspicion of those who spotlight the Asianness of our bodies – to alienate, manipulate, romanticise, or extract cheap labour from.

The timeline of our friendship is littered with stories we have about this, before and after we met each other.

There arises the opportunity for the postcolonial exotic to enact a “fakery of representation and the faking of the real”.7Maria Takolander, “Magical Realism and Fakery: After Carpentier’s ‘Marvellous Real and Mudrooroo’s ‘Maban Reality’”, Antipodes 24 (2): 165. That is, a Southeast Asian woman of small stature and fairly unassuming appearance can capitalise on others’ assumptions of her submissiveness, timidity, and good intentions to get what she wants – even things she doesn’t ask for. This racial privilege foists her upwards in a caste system of the Western public imagination, which places South Asian, Middle Eastern, Bla(c)k and First Nations women and femmes below her. It makes her complicit in the system, and that’s probably why we’re still planting this essay in an earth raked dry of Asian-Anglo musical critiques.

Neither Kim nor Cio-Cio San have friends. Genuine friendship is hardly part of the geisha or bar girl trope. It is in the aftermath of heartbreak or disappointment, in the therapeutic healing of shame or nightmare, that we are encouraged to speak to others. The value of a network is that it enables conversation and support. I do not advocate for complete erasure of historical artefact, but I do advocate for more nuanced critical thinking regarding how we protect the historically marginalised from being further brutalised by the colonial violence that Madama Butterfly and Miss Saigon embody. This requires ongoing conversation, and often the warmth and openness of friendship between communities of this socially constructed ‘Asian’ continent.

When something is made singular – to be priced, put on display, or sold – it becomes fetishised as a commodity. Alongside conquest of land comes the conquest of flesh. In White Tears/Brown Scars, Ruby Hamad examines the index of “lewd jezebels and exotic orientals… angry sapphires and dragon ladies”, arguing that this spectrum of carnal, animalistic and sensation-driven creatures, projected onto particular races subjugated under European powers, produced both disgust and desire in their captors.8Ruby Hamad, White Tears/Brown Scars (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2019), 24-35.

However, these jezebels and orientals and slaves survived on alternate kin networks with others who shared their plight. Women, slaves, lower classes, and migrants, while siphoned by their masters into the lowermost foundations of Western society, “in many ways… provide one of the richest archives of friendship practices throughout history”.9Celine Condorelli and Avery F. Gordon, “The Company We Keep part one,” in The Company She Keeps (London: Book Works, Chisenhale Gallery, 2014), 36. In the worlds of plantations, theatres, and bathhouses, workers were often severed from their former selves by the conferral of a new name to perform under. In Spirited Away (2002), the child protagonist Chihiro also loses her true name given by her family, when her employer, the witch Yubaba, takes it as a contract for her employment at the bathhouse and issues her with the name “Sen”. As a coming-of-age film, it explores the significance of naming (or forgetting one’s true name) as one leaves childhood and enters adulthood as a worker, exchanging their body in transactions and contracts for some semblance of safety in a disorientating new world. Enduring friendship however, allows Chihiro’s true name to be remembered. Friendship proved a necessary salve for the violence of labour and unnaming, and a means of survival, solidarity, and secret-keeping. The name that your master discarded was salvaged by your friends.

ACT 3: THE CURTAIN FALLS // HOW HEAVY IS A DREAM?

ACT 3, SCENE 1: A GRANDMOTHER’S WARNING

I cannot help but wonder about the motivations of my late grandmother. As a woman of English descent, perhaps it was her way of relating to me, to share a story that she believed was distinctly ‘Japanese’, or perhaps she was pointing to a lived reality that I may face of being exoticised, or, as written by Edward Said in Orientalism, into being made one of those “creatures of a male power-fantasy. They express unlimited sensuality, they are more or less stupid, and above all they are willing”.10Edward Said, Orientalism (New York City: Pantheon Books, 1978), 207. Since the 19th Century, the Madama Butterfly archetype has continued to flap its wings, and has spread a blood-moth stain across pop cultural references over the past century.

This is written in the genealogy of ‘unbelonging’ which is apparent in linguistic meditations of both Asian American and Asian Australian history. The pervading trait of Asianness is to be invisible: double erasure through demarcations that included the White Australia Policy and immigration restrictions. Japanese women who met their future husbands in Occupied Japan under the strict anti-fraternisation policy would undergo a migration period in Australia post-WWII under the White Australia Policy. From there, they began the process of assimilation, with many families masking their origins from fear that they would be ostracised – despite already being barred even from owning land by the policy. A war of attrition began when these women set foot on foreign soil – their tongues stolen and silenced.

間 pause

Working as a dancer and collaborator on many projects after dance training and university, there have been occasions where my dancing body has been called ‘exotic’. One particular encounter that stayed with me was with a European choreographer. He once told me women dancers were typically either ‘beautiful’ or ‘talented’ but very rarely both, and it was up to me to decide which one of the two I would be. While this was not explicitly a comment about race, the choreographer took particular interest in my Japanese heritage. He was continually drawing from Japanese perspectives on eloquence and nature in his work.

I tried to make light of the comment at the time, but it seems to recall what is now emerging with #StopAsianHate: the reality that racism and misogyny are inextricably intertwined. Can this bodily practice ever forsake the hypersexualisation of my body? In forsaking it, could it retain sexuality?

間 empty

I think of 間 ma—the space between things, the gap, the pause. It is the invisible but discernible warmth between a couple, it is the comfortable silence that fills a conversation between friends. The way of sensing the moment of movement, a ‘no-man’s land’ where formless energy enters and fills the crevice.11Cheryl Stock, The Interval Between…The Space Between…: Concepts of Time and Space in Asian Art and Performance (2005), in Sarkar Munsi, Urmimala, Eds. Time and Space in Asian context: Contemporary Dance in Asia. (World Dance Alliance), 17-38. It is the feeling at the end of a dance. It is a feeling of aloneness, a space where emptiness and fullness co-exist, a dance of fragility and strength, great happiness and despair. The end of an opera, but so too its legacy, is another musical that exists in no-(wo)man’s land.

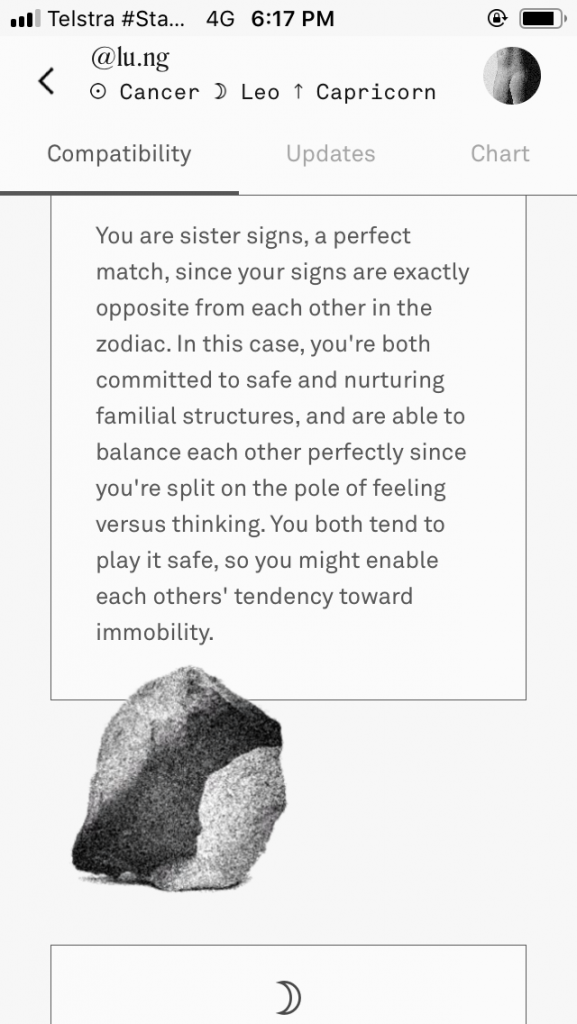

ACT 3, SCENE 2: MISS SAIGON

Sometimes I wonder why Reina and I love to talk about omens so much – the nebulous (often senseless) edicts lighting up our phone from Co–Star, the nagging fears every time our love lives shift, the dreams and premonitions we often try to interpret together. Astrology, premonitions and the inexplicable workings of love fall into the spectrum of magical realism, where the lines of demarcation that separate what is real and what is fantastic are often blurred, forged or scattered. But these memories belong to us, and no one else.

One evening, I walked to the Museum of Contemporary Art to watch Reina perform a piece called ‘Holding Lightness’, choreographed with two dancers of Southeast Asian descent. A minefield of citrus fruit, papayas and dragon fruit is laid in the gallery foyer, which her mother tells me was inspired by fruit tumbling from the fridge during an earthquake while Reina was in Japan. Rallying against harmful, neocolonial representations of our bodies is a minefield (of ideological backlash, not tropical fruit), particularly when we comply to some degree.

Often Southeast Asian Australian writers, specifically women, find magic realism to be a powerful literary mode because it straddles “the ‘actual’ and ‘imaginary’… situated in-between resistance to, and collaboration with, Eurocentric modes of representation”.12 Giffard-Foret, “Southeast Asian Australian Women’s Fiction,” 675. Association of the feminine body with the cosmological world (with fruit, animals, the stars, and moon) exists in tandem with the rise of patriarchy and the rise in ownership of private property, when women became otherworldly creatures to bridge the distance between Man and Nature. The Oriental woman embodies this perfectly, being owned both physically and mythically.

I like to think the stars will tell us otherwise.

EPILOGUE

友達 friendship

You are sister signs, a perfect match,

Since your signs are exactly opposite from each other in the zodiac…

I dream of ancestors’ bones held

Inside the belly of a sound,

With the brutal weight of gravity bearing down.

We are now the sound,

The sounds of laughter,

And radical joy bubbling from an orange hearth.

Photo by Valerie Bong

We wonder, if Miss Saigon and Madame B had met, whether they would have been friends, whether they would have sent each other their Co–Star updates. We wonder whether they would have debriefed about their love lives and, perhaps, even avoided their tragic demise.

Perhaps the opera of friendship just doesn’t sell.

Though maybe that’s the point. You don’t need to make something simply for it to be sold. Sometimes, we need to make things for ourselves. In a dance, a spar, or a conversation, we move and breathe and scrawl across space with our bodies. Kinship renders these movements legible to others who keep our secrets and our stories. It is sweeter to share a piece of fruit, even if others have historically deemed you to be worth no more than something to be harvested and eaten.

But what does it mean to right a wrong from the beginning? Is our potential as women limited by these operas, or do they give us even more power, however deviant that may be?

Tethered through friendship,

Anchored to gifts of new confidences

And experiences

Storied women before us never had…

If women hold up half the sky, they can play with the universe.

END

Reina Brigette Takeuchi is an artist-researcher, curator and dance maker of Japanese-Anglo Australian heritage whose practice spans visual arts, choreography, curatorial projects and writing. Influenced by her peripatetic upbringing across Asia and South-East Asia, she uses an auto-ethnographic approach to meditate on transculturation and lived experiences of displacement. She has contributed to publications including Ausdance Qld, Delving into Dance, Eyeline Contemporary Visual Art magazine, 4A Papers and Runway Journal.

Lucia Tường Vy Nguyễn is a Vietnamese-Australian writer exploring the intersection of Southeast Asian folklore, ludic violence and global technoculture. She has been featured in publications such as Kill Your Darlings and Runway Journal, and was selected for Writing NSW’s development program for emerging editors in 2021. She is invigorated by the opportunity to play and dream within, around, or even outside capitalist structures of “work”.

*

Edited by Joanna Guelas. Jo is a journalist living and working in Naarm. They started as an editorial intern at Going Down Swinging in 2021, and is currently in her second-year of her BA (Media and Communications/Politics) at the University of Melbourne. Her work has been published in Farrago Magazine, Gems Zine, and Kindling&Sage. They’re incredibly passionate about investigative journalism, Richard Siken’s poetry, and the Melbourne Football Club.

FURTHER READING

Australian Government. National Opera Review: Discussion Paper. Accessed July 2, 2021, https://www.arts.gov.au/have-your-say/national-opera-review.

Condorelli, Celine and Avery F. Gordon. “The Company We Keep part one.” In The Company She Keeps, 33-43. London: Book Works, Chisenhale Gallery, 2014.

Giffard-Foret, Paul. “Southeast Asian Australian Women’s Fiction and the Globalization of ‘Magic.’” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 50, no. 6 (2014): 675–687.

Hamad, Ruby. White Tears/Brown Scars. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2019.

Huggan, Graham. The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Johnson, Barbara. “Muteness Envy.” In The Barbara Johnson Reader, 200–216. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020.

Kanomori, Mayu. “You’ve Mistaken Me For a Butterfly.” AboutOkin. Accessed July 2, 2021, https://www.aboutokin.com/2016/02/11/madama-butterfly/.

Nikkei Australia and Tamura, Keiko. “Life Story of Cross-Border Women: Japanese War Brides in Australia & Interview with Alumni.” Nikkei Australia. https://www.nikkeiaustralia.com/lecture-keiko-tamura-life-story-of-cross-border-women-japanese-war-brides-in-australia-interview-with-alumni/.

Park, Patricia. “The Madame Butterfly Effect: Tracing the History of the “Asian Woman Fetish.” Bitch Media, July 30, 2014, https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/the-madame-butterfly-effect-asian-fetish-history-pop-culture.

Pham, Victoria. “Opera Australia and the Expense of Orientalist Spectacle.” Decolonial Hacker, August 23, 2021, https://www.decolonialhacker.org/article/opera-australia-and-the-expense-of-orientalist-spectacle.

Piper, Christine. “About – Loveday Project,” Loveday Project: Japanese Civilians interned in Australia during WWII. Accessed July 1, 2021, https://lovedayproject.com/about/.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York City: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Song, Elise. Asian American Sex Workers Book Club. Teachers College: Columbia University, 2021.

Stock, Cheryl. “The Interval Between…The Space Between…: Concepts of Time and Space in Asian Art and Performance.” In Time and Space in Asian context: Contemporary Dance in Asia, edited by Urmimala Sarkar Munsi, 17-38. Kolkata: World Dance Alliance, 2005.

Takolander, Maria. “Magical Realism and Fakery: After Carpentier’s ‘Marvellous Real and Mudrooroo’s ‘Maban Reality’.” Antipodes 24 (2): 165–171.