In my first share house in Melbourne, I found a black worm in the bathtub, stuck to the side, curled in foetal position. The idea of it inching its way up our pipes then waiting to unravel made my stomach coil, made the floor I walked on feel angry and dirty. I found bleach in the bathroom cabinet, and poured it on the worm’s soft, unarmoured body. It slipped through the cracks of the plug hole, and only then, after the room began to soak with the smell of an indoor swimming pool, did I undress.

ς

I’m telling my friend Maureen about this aversion to worms; I want to dig it up, dissect it. Everyone else I have talked to voices their outrage. My father says, but—but—worms are the friends of the earth! David, who I live with, says, but don’t you think they’re good? Like, objectively good? Maureen is the only one who sympathises. There’s something repulsive about them, she says, about their helplessness! Maybe we see ourselves in them, and we’re repulsed by it, you know?

ς

When I say I’m haunted by worms, I mean the kinds that crawl on their bellies, the kinds with no faces, no eyes, nothing to show their discomfort. The worms that burrow in my mind have no name, no common genus, but they all share the movements of something spineless and thin. They are the earthworms my father digs up from the ground; they are the knots I stumble through in my dreams.

What horrifies me: a worm thrashing when exposed to light. Its silence, its feeble protest. How its pink resembles human skin.

ς

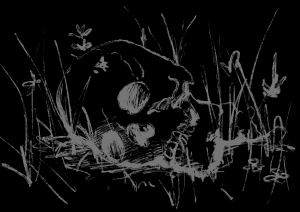

In my last year of high school, worms began to appear between the floorboards in our kitchen floor. I found my mother one morning hunched over the floor, toothpicks scattered around her. One of her feet was in the thick sole of a walking boot, the other naked and undone. There was something fragile about her bare foot, about her back, curved like an egg. For a moment, it looked like she had simply fallen and given up.

What are you doing? I asked, before I noticed a blue pan in her hand and white entrails wriggling on its surface. With horror, I watched my mother dig a toothpick into the seams between the floorboard, unearth a writhing thing. She primly dropped it in the pan and looked up. Worms, she said, answering a different question. The worms were small—not pink, fleshy earthworms, but pale and barren, white commas in blue text. If I stared at them hard enough, I began to question if they were moving at all. Watching their bodies squirm on the blue pan, metres from my face, I was filled with a nausea of eating too much, of standing up too quickly: vertigo. I ran to the bathroom to wash my hands once, twice, tried to scrub the sweaty brokenness off me.

From the Medieval Bestiary: the worm does not move with distinct steps, but by stretching and contracting its body.[1]

Something base about a body pumping—not the effortless gallop of a horse, nor the bounding of a dog. A worm moves in painstaking strokes, applies energy in a manner that is laborious, time-consuming, undignified. We say things like, he wormed himself into their lives, or I wormed a few details out of her. In both instances, the worming is an act of trying again and again. In some instances, the worm also squirms. It squirms in silence, when it’s restless, when it wants to make known the aliveness of a body trapped. It’s a movement of utter helplessness and not wanting it to be so.

ς

After that morning, I routinely inspected my navel and my eyes. I became half-convinced that worms could invade me, become parasitic. There are worms I knew of that depended on encounter: the hookworm, whose symptoms were innocuous and can go undetected, or the ancient guinea worm, which announces itself in the form of a blister, a burning, singing pain one year after infection. There are worms that swim in your eyeballs, that you can pull from your belly button. There are worms too small and thin to distinguish from a thread of string. On those nights, before sleep, I imagined my mother’s toothpick flung wrong, a worm sticking to my skin—becoming, magically, absorbed. Then I would reassure myself, quieten my mind by replaying that scene again like a talisman—of my mother stooping, extracting small commas from the floorboards.

ς

There is a fifteenth-century painting of Job, titled Job on His Dunghill Infested by Worms.[2] It’s an accurate title. Job’s flesh sags, while papery, white trails tug away at his loose skin. The cause of Job’s suffering is a mystery. Some say God wanted to test His beloved; others say God was taunted by Satan until He allowed Satan to test Job. In any case, Job is robbed of his sight, his children, his livestock, until finally, his ‘flesh is clothed with worms and dirt’.[3] In the painting, Job’s expression is blank, his eyes are numb. His body is an image of God’s love (in the past) and God’s test (in the present). One arm supports his lolling head, the other rests on his knee. I imagine the worms all over his body squirming frantically, while he silently decays. It’s the contrast—the worms’ squirming and Job’s stillness—that makes the painting so unnerving.

See, if I were Job, I would excavate those wounds, run to my mother for her to dig that ‘shit of the earth’[4] out immediately. If it were me, I would douse myself in hot showers, unzip my skin, dry it out in the sun for the light to exorcise. I would try to forget.

ς

In Konrad von Megenberg’s Buch der Natur, he distinguished the vermin that crawl from the vermin that fly.[5] In a hierarchy, bees, flies and moths soared to the top because they were closer to the heavens, closer to God. At the bottom, weighted to the ground, worms ‘arous[ed] both disgust and fascination’.[6] If closeness to the heavens were synonymous to degrees of spirituality, then worms were condemned to heresy. In all my imaginings of Job, he lies on the ground, sagging. His friends approach him, tall and upright. Instead of lamenting his loss and suffering, they nag, hurl platitudes at him, and eventually leave. Confronted by his humiliation, why wouldn’t they turn away? To stoop to Job’s level would be to encourage their own suffering, invite it even. So they turn away—in relief and with distance, that the suffering is not theirs to bear.

ς

Most often, I am repulsed by a worm’s vulnerability, its susceptibility to pain. I’d rather not show my forsakenness; I’m like Job’s friends, turning away.

In primary school, there were friends of mine who, after rainy days, fashioned sticks to pick up stray worms that were caught drying out on pavements. They did this out of some innate desire—to rescue, return the stranded worms back to the soil. But no matter how I rationalised and cajoled myself, I couldn’t look, let alone help. Look, David says, after a rainy morning. The ground is alive with terror, with their squirming bodies lying in gutters, and I feel myself slowly sink. No other movement creates such violence in me.

In the book I’m reading by Tessa Hadley, a marriage is dissolving. The wife appears calm, self-sufficient, to her now-estranged husband. He, feeling a surge of reconciliation, of wanting to hold her in his arms, ‘remember[s] the cool self-sufficiency with which she’d said goodbye’,[7] and stops. But earlier, she had tried to write to him. Dear Alex, I feel so…Dear Alex; I can’t get over…I feel crushed. Alex, I know I haven’t been…I’m recounting this narrative to David, and with horror, I realise my voice is trembling. It would be funny if it wasn’t so awful. It’s just so sad, I say, and I hear my voice yelp. I am going to become undone. David’s voice comes from somewhere faraway: are you projecting? Wen-Juenn, I think you’re projecting.

ς

Sometimes, I think my parents’ roles were to protect me from feeling wormy. They tried to give me armour, a good education, an ability to overcome problems and hardships. But there comes a point, I have realised, that one must accept, surrender even, to being soft and forsaken.

Most often, I feel close to the ground when I am on my period, when my spine concaves, when my body hurts me from the inside out. I slouch and bend, try to stop the hurt from pervading outside.

This is what my friend will notice the first time we meet. She studied physiology, and she remembers a person’s posture the same way others remember faces. Later, I will ask her: what did you notice about me? and she will bend her index finger at the knuckle, like a spine deflating, like a worm curling inside a bathtub.

On fragile days, I don’t want to touch or be touched. I feel like a worm, I text a friend, uncharacteristically honest. They reply: we are just two worms hugging!!!!

ς

In that moment, before bleach, before plug hole, I had been caught in an unarmoured state. I needed to humiliate, expunge materiality from my system. Grace Lee writes of a body ‘with not a wisp of excess’, swallowing ‘a tyrannical myth of cleanness’.[8] To become ephemeral, spectral, to refuse the earth I am weighted to, bound for. The desire to depart from pain, and on the cusp, see something like dirt.

ς

There used to be a statue of a giant earthworm, Kathy Holowko’s Unsung Hero, curled in the middle of Edinburgh Gardens.[9] Up close, you could see the bands of lines on its body, its distinctive facelessness instead of a colonialist on a plinth. On a bad day, biking past, it would unsettle me. I would avert my eyes, as if it would surge to life, turn its blank face towards me.

Tessa Laird said: Kathy takes what is usually under the plinth, and puts it on top…spotlight[s] to that which is usually hidden, and where we have to pay respects to that which we take for granted.[10]

Derrida said: In the beginning, there was the worm![11]

Underneath the colossal daylighted earthworm, I imagine thousands replenishing soil in their tunnels. Agents of life, custodians of dead and dying things. How, only on rainy days, they rise up like silt—to be seen for once. How, underneath, in the dark, they are like gods churning the earth.

ς

Every time I’ve told the story, the worms in the floorboards were bad omens I needed protecting from. They were harbingers of decay—the end of school, not the beginning of university. But if I were a farmer, worms would be a blessing—a sign of good crops, a bountiful feast, a prosperous future. Later, we came to the conclusion that the worms in our floorboards were maggots, born from insects that lay eggs in the wood. They were signs of new life, just not the life we wanted. And for my mother, she was able to live with it, still dropped to the ground in the middle of tying up her shoes, abandoned her walk to dig. Every morning, she still rises to walk up Mt. Kau Kau, visits the glow worms that light up the damp bush at dawn. For a few metres across a bank, the glow worms blink like mini constellations. They’re the only light you can see under a dense canopy, guiding you along the path. Later, when we’ve all woken up, and she’s describing their beauty, I imagine the worms blinking blue like lights on cranes, warning aircraft not to crash. Please be safe, they’re saying, this is my wish for your future.

ς

When I think about the worm I poured bleach on, I think about how it began its journey to my bathtub, how it found itself in our pipes. How it twisted, contorted, until it broke through, into somewhere hard and tiled. I don’t know if I would do it again; but when I look down plug holes, I can still taste the acidity of my revulsion, at the worm, at myself. I don’t know what it felt, moments before, but I know what I did. I wanted to feel clean again in the sanctity of a bathroom. I wanted to wash the grime and dirt that clung to my unarmoured skin, to settle into pyjamas and slip between fresh sheets. To fall asleep, curled on my side, and dream easily.

ς ς ς

[1] Isidore of Seville, De etymologiarum, Book XII, Chapter V, Bibliotheca Augustana.

[2] Guyart des Moulins, Bible Historiale, Paris, early fifteenth century, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, MS fr. 9, 18.375 x 14.375 in (46.5 x 36.5 cm), Folio 244: Job on His Dunghill Infested with Worms.

[3] The Bible. The New Jerusalem Version, Reader’s Edition. Darton, Longman and Todd, 1990. Job 7:5

[4] Souvankham Thammavongsa, ‘Worms’, Ploughshares Vol. 44, No.4 (Winter 2018-19), pp. 153-160.

[5] Thomas of Cantimpré, De natura rerum, German translation by Konrad von Megenberg, Hagenau, c. 1442-48, Universitätsbibliothek, Heidelberg, Germany, Cod. Pal. germ. 300, ‘Book XII: Of Worms’.

[6] Rémy Cordonner, ‘Vermis: The Worm’, in: Christian Heck and Rémy Cordonner (eds.), The Grand Medieval Bestiary: Animals in Illuminated Manuscripts, New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 2012, pp. 577-578.

[7] Tessa Hadley, Late in the Day. Vintage, London, 2020.

[8] Grace Lee, ‘Body/Love’. Paula Morris and Alison Wong, ed. A Clear Dawn. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2021.

[9] Kathy Holowko, The Unsung Hero. 2019, Yarra City Arts, Melbourne.

[10] Tessa Laird, ‘In Praise of the Worm’, Launch of The Unsung Hero. Yarra City Arts, Melbourne. October 20, 2019. Launch event speech.

[11] Jacques Derrida and David Wills. ‘The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)’. Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter, 2002), pp. 369-418.