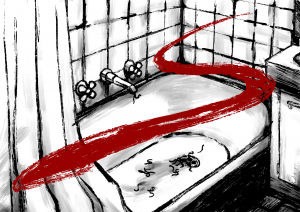

There’s no coitus in Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, possibly the most notorious art-house film about erotic love and loss.

Well, there is. An affair has happened, and the shock of it is what leaves the cheated-on protagonists, arguably big-screen history’s most beautiful infidelity survivors, finding solace with each other.

It’s a story of solidarity, of the way stories make and unmake, of infinite retellings in a world of finite opportunities. The love story begins with the shared experience of betrayal. Chow Mo-wan ‘Mr. Chow’ (played by Tony Leung) and Su Li-zhen ‘Mrs. Chan’ (Maggie Cheung) play-act the moment of when the affair between their spouses began. What if he made the first move, what if she had instead? The storytelling play extends to Mr. Chow returning to his childhood dream of writing martial arts serials. He gets Mrs. Chan to be his co-writer. Long hours are devoted to their collaborative world-building. There are more scenes with shared meals than there are of any physical touching. There may be something deeper about this kind of sharing. To eat is to consume. So is looking into someone’s eyes, to be lost and found, to lose and to find, in an act of simultaneous exchange and theft. To touch not the skin but the spirit, through imagination, through putting things into words, to holding space for the unsaid, together.

In a different world, they would have fucked. I see that story ending more pathetically, however, than the tragedy of the story played out as we know it: they way they keep missing each other despite being in constant proximity, how they know there is love between them, but never get to do the quotidian couple-things other socially acceptable couples take for granted, like holding hands in public or massaging each other’s feet before sleep. They do a few wonderful things that not many couples do successfully, like cultivate what appears to be an effective creative collaboration; the sort of thing that, when handled poorly, sometimes rips relationships apart. The whiff of scandal constantly shadows their little stolen joys. Some people get off on the risk of discovery, but what these two long for, even beyond their longing for each other, is bourgeois respectability. To be able to go to work, or return home to tight apartment spaces with nosy neighbours, without being heckled about things they’re doing with people they shouldn’t be doing them with. It is an unconventional intimacy, and they are conventional people.

The opening sequence of In the Mood for Love has the lines: ‘It is a restless moment. She has kept her head lowered… to give him a chance to come closer. But he could not, for lack of courage. She turns and walks away.’

I sometimes wonder if theirs was more of a trauma bond than a love that had long-term potential, beyond the shared ache of rejection and humiliation that surviving infidelity brings. If they didn’t have their pain, could they still be what they were to each other?

~

I was 14 when I met the first man to talk to me about Plato. Let’s call him Juan. Juan was a literature tutor. We’d encountered each other briefly offline before continuing the conversation online, mostly emails, and then later, calls. I had feelings for him – the first time I had strong romantic feelings for anybody. He would tell me, three years later, that he didn’t feel the same way.

He had gotten a scholarship to do a PhD in Belgium. A legendary place to study philosophy, he said. He tried and failed to teach me French. What was it he said to me about Plato, about PhDs? Something about beauty, something about love, something about reading everything everyone else had written, and then trying to say something that hadn’t been said before. I was 14, in my first year of high school. He had just graduated from university.

Juan told me he’d been a theatre actor throughout high school and university. It helped him with his rage issues. He grew up working class in a country town, went to a private boys school and a leading university on a scholarship. That was to become my own story too, moving to Melbourne for scholarship-funded university study, although I did not realise it yet at the time. We don’t talk anymore, so when I think of him, I fill in the blanks with my own experience. Being an actor is about being on display on someone else’s terms. Your body and soul are at work, but unless it’s a show you wrote, it’s the director pulling the strings. If you’re good, you get credit – for embodying someone else’s vision. If the role is good for you, it’s an opportunity to say everything you needed to say, but only through someone else’s story.

I was 14 and Juan was 20-something, straight out of his bachelor’s degree, heading to Europe for his PhD. It wasn’t a relationship, but maybe it was. There is an old TV show called Nip/Tuck, about plastic surgeons and their clients and the messy lives beyond the clinical certainty of the scalpel. One of the surgeons has a line: ‘When you’ve seen someone’s cum face, you’ve seen their soul.’ I wonder if the reverse applies: if you’ve seen someone’s soul, is that like seeing their cum face? I read Plato’s Symposium years later. Much of it reads like an endorsement of hierarchy-based relationships, specifically between older men and barely bearded boys in this specific socio-cultural context, following the idea that perfection is unattainable but the temptation of perfection spurs one into excellence. I’m not a philosopher so I could be missing the point. The elder is wise but not beautiful, probably lonely, and the younger – beautiful but raw and definitely not wise. The elder takes on the role of the lover, the younger the love-object, the beloved. The younger is drawn to wisdom, and flattered by being thought worthy of attention. I imagine that for someone with a lot of wisdom but not lot of prospects, someone looking at you like you have answers is a thrill the ego never gets used to. That another human could find your mind so interesting. The elder, wiser lover and the younger, more foolish, more beautiful love-object, exploring their humanity together, fumbling through books, fumbling in other ways. It wasn’t a relationship but what if it was? I only realised this years later, when it occurred to me that his sadder – or simply more quotidian – stories about life as a Filipino international student in Europe were things you only tell someone you trust, someone special to you. If we didn’t have our pain, what else could we be to each other?

Many years later, the second man to talk to me about Plato told me about Penia, the goddess of poverty, who in Symposium comes to a party as a beggar, fucks Poros, the god of wealth, and gives birth to Eros. Eros, simultaneously an experience of hunger and fullness, longing and satisfaction. A love story so real it could have happened at Colour Club.

I’m halfway through Alenka Zupanćić’s What IS Sex?. If you ask me right now what the book is about, without grabbing the book, this is what I would say: Sex is more than merely coitus, it’s something we approximate through language, but can never be contained within it. Sexuality is what happens when we fill in the blanks.

~

It takes only one person for a relationship to end, but two to make it work.

I believe it was the relationship therapist Esther Perel who said it takes a village to raise a relationship.

In the commons of Instagram-style relationship theory, I see statements like, ‘You can’t be each other’s whole worlds.’

I don’t know of any deep love that didn’t begin with wanting to be somebody’s whole world.

Juan gave me a copy of Ray Bradbury’s short story ‘The Fog Horn’ just after my first year of high school ended. It is to this act that I owe a lifelong erotic vulnerability to people who tell me what’s worth reading. These lines: ‘That’s life for you. Someone always waiting for someone who never comes home. Always someone loving some thing more than that thing loves them. And after a while you want to destroy whatever that thing is so it can’t hurt you no more.’ The story is about a lonely sea creature, told from the perspective of an apprentice to a lighthouse keeper. Love will keep you alive, like an old song goes, but love, like hunger, can also kill you. Or turn you into a monster. I still get chills on my arms every time I read the ending.

~

Elementary is probably my favourite TV show about intimacy without fucking.

This telly retelling of the classic Sir Arthur Conan Doyle book series is set in New York, starring Jonny Lee Miller as British expatriate and recovering addict Sherlock Holmes, and Lucy Liu as Joan Watson, his sober companion, disgraced former surgeon, and eventual co-conspirator. I liked it more than the more classically British Sherlock, and not just because we see in Elementary what’s so rare on English-language television: a woman character of Asian descent be more than a sexual conquest or unremarkable sidekick for a mediocre white man. Elementary is about what it’s like for two people who love each other, to live with each other, collaborate closely on a lifelong adventure, without sleeping with each other, or succumbing into an unrequited romantic tragedy.

Joan enters Sherlock’s life as his sober companion to aid in his recovery from substance addiction. She is intelligent, accomplished, compelling, beautiful, age-appropriate, and sexually unavailable by virtue of their professional relationship. Sherlock, a libertine, has to find a new way of relating to her – and to his commitment to sobriety. Their collaborative detective consulting projects enable them to be together in a way that empowers Sherlock to maximise his cognitive talents, without giving in to the risk of addiction.

The work gives Joan a framework for coexisting with Sherlock beyond the societally approved ways two people can be together: as intimate partners, spouses, siblings, family, or mere house mates. Friendship is a word that applies here, but in the show they refer to each other as partners much more often. ‘Partners’ can be a word for romantic intimacy, but for Sherlock and Joan, it is an intimacy beyond romance.

I worry about the risk of the ‘I can fix him’ trope, when a woman engages in a co-dependent relationship with a troubled man, in the hopes of being The One who salvages the best of him, rewarded with a happy lifelong romance in the end. In Elementary, it’s different. Joan’s mere presence in Sherlock’s life is what inspires him to take responsibility for his mistakes and his growth. Whatever she does with or without him, the existence of their relationship sustains the energy he needs for his recovery.

In the finale, Sherlock speaks to their common friend Gregson about his anxiety about being in Joan’s life now that she’s adopted a little boy. ‘I worry he’ll find me dead with a needle in my arm, and then what?’

Gregson tells him Joan has cancer, something she kept from him. ‘If you love someone big enough,’ Gregson says, ‘you can let them choose to be with you.’

Unlike Wong Kar-Wai’s tragic heroes, these two have always had the courage.

~

Dark and dangerous like a secret

That gets whispered in a hush

When I wake the things I dreamt about you

Last night made me blush

And I feel it like a sickness

To be weakened like Achilles

with you always at my heels

Juan emailed me these song lyrics once. A strange way to discover the Indigo Girls. This happened not long after he bought me an art book about Van Gogh, and told me not to tell our mutual friends. We only started talking about Van Gogh because of that famous Don McLean song ‘Vincent’. I told him I liked the poetry. He told me these lines made him think of me:

For they could not love you, but still your love was true

I could have told you Vincent

The world was never meant

For one as beautiful as you

Until that time, I loved him while believing he didn’t love me. I knew I was too young. I thought he was in love with someone else. Why he would send verses like this to a teenager is beyond me. I knew I was in love but I also knew I wasn’t ready for a relationship beyond the emails and calls. I needed to know where his head was at. I asked him to call me from overseas. On the phone, I told him how I felt about him. He told me he didn’t feel the same way. We still kept talking after that, until he started making a big deal about me being too young. It made me feel like he thought I demanded more than I did, that he had no responsibility in the way this relationship had turned unruly. We stopped speaking not long after.

Several weeks ago, I saw his name in overseas newspapers. He was a named party in sexual assault allegations.

It’s been a long time since we last spoke, and I’ve long gotten over the feelings I once had for him. But with this news, what do I do now with the memories? I hope the students he harmed are getting the support they need. Was I was the first in a pattern, and how does he live with himself now? I don’t know if I’m making excuses for his behaviour by sometimes wishing I could ask if I was the first, wondering if the years between us were an honest mistake. I don’t know if I’m a horrible person for wanting to know if he still thinks of me.

~

Something about beauty, something about love, something about reading everything else that’s been written, and trying to say something they hadn’t said before.

Guys who send me alternative rock dad songs. Guys who give good ancient Greek references. Guys up to 10-ish years older. Muses. Monsters. Secret loves and losses. If all love is derivative of the first time, it might be a good idea to examine what all loves have in common with the first time.

The first time I tried telling Juan what I felt for him, it felt like I was being told I was asking for it, like I was blamed for having these emotions, and also like I was not being entirely truthful about what I wanted. This might be why I don’t put myself out there romantically or sexually, why I never want to be the one who says, ‘I want you’ or ‘I want you like this’ or ‘I like you but I don’t want anything beyond this.’ Why writing feels more comfortable than speaking, and not just because of that generational anxiety about phone calls. It’s easier to listen to, or write about, people doing love well, or not well, than it is to live it. To speak one’s truth through other people’s stories, like an actor, sometimes, or a critic. ‘If you love someone big enough, you can choose to let them be with you,’ Gregson told Sherlock. I wish I could know how to allow myself to be moved by someone without being broken by them.

An early topic of conversation with a psychoanalyst was Jacques Lacan’s phrase: ‘Love is giving something you don’t want to someone who doesn’t need it.’ The discussion revolved around me constantly messing up the verbs. If you read a lot of Lacan, you’ll see I’ve gotten the words wrong again. Maybe that says more than being right. If love is hunger, it’s a weird thing to want to give somebody. But I can’t imagine what it’s like to live, to grow, and to die, without having someone you’d miss.