For most of my adult life, I have believed that tenderness is a virtue. That if you can move through the world in touch with your emotions, you will be able to resist the some of the uglier shapes capitalism presses us into. No one had told me you could walk around being openly sensitive – not only having a lot of feelings, but telling your friends and family about them. I thought it was weird, and then I started practising my own beta-version of radical vulnerability, mostly pieced together from things I read on social media without much engagement with the serious intellectual works underpinning it. The results were still surprising: I felt better, then okay, and then sometimes even good. So I adopted it as personal philosophy, failing to ask any of the hard questions I should have.

But I am done with being tender. On a long coastal walk with a friend I tried to explain my reasons, but I was crying too much to say what I meant. I was at the tail end of another break-up and, in the words of Blood Orange, was praying for my heart to turn to stone. My friend told me that it hurt right now, but the pain would ultimately make my heart stronger. It is a muscle, she said, like any other, and mine was getting a very good workout. In fact, she wished she had the courage to exercise hers more vigorously. I tried very hard to believe her.

One of the most recognisable artists who seems to endorse a philosophy of tenderness is Jenny Holzer. Her work appears on my feeds often, usually in posts about reclaiming my feminine power or advertising exorbitantly expensive co-working spaces in which “women support other women” over glasses of complimentary cucumber water. But her work transcends the more banal corners of supposedly feminist social media. They are also widely shared by artists and poets I admire, the sort of people that always seem to be wearing linen shirts and wandering through fields tinged in some peach shade of sunset. I like to think her work’s popularity speaks to its conceptual universality, but I have been wrong about this before.

Holzer’s original artworks were often posted around cities: on billboards, above theatres, even projected onto the sides of buildings. You probably recognise some of them: ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE. Or maybe her Inflammatory Essays, which I have seen in the form of a pink postcard above so many of my friend’s beds with the line: THE GAME IS ALMOST OVER SO IT’S TIME YOU ACKNOWLEDGE ME. But there is one work in particular I’m interested in, from Holzer’s 1983–85 Survival series. Initially posted above a theatre in huge black letters, it reads: IT IS IN YOUR SELF-INTEREST TO FIND A WAY TO BE VERY TENDER.

This work might be one of the earliest examples of what I’ll call an “aesthetic of tenderness”. The look of Holzer’s messages – the capitalisation, the use of pastel backgrounds – lends itself to social media, even though she was working long before it existed. This aesthetic has been copied widely by other artists, reproduced on mugs and tote bags and posters using different words but communicating the same basic message: emotional vulnerability is a form of resistance to patriarchal capitalism. I understand the logic on a personal level. If we are part of a system where even art is shot through with capital, what does it mean to resist? Making art is not enough; making money is not enough. And anyway, to fight that kind of system on its own terms risks turning you into the very thing you hate. Some radical feminist thinkers tried to find another way.

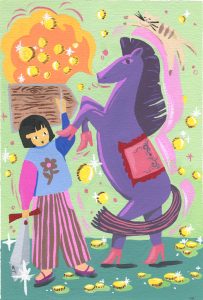

One morning when the worst of my break-up was over, I woke too early at 6 a.m. and had one overripe peach and a glass of cold coffee. The acidity on my tongue dredged up an afternoon in summer when he and I bought peaches and cycled to the meadow. It took us twenty minutes at the supermarket to find a bag worth buying – he asked one of the men packing shelves if they had “a secret supply out back”, which was the kind of thing he always asked. With a wide enough smile, it worked often. By the time we got to the picnic spot, half the peaches had split open. We ate what was left, laughing, and I said, “This might be the worst thing that has ever happened.” I won’t lie and say the fruit tasted good, but they were peaches, and that was enough.

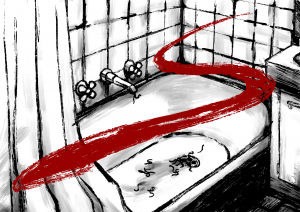

My friend Phoebe Stuckes wrote a poem which opens, “The word tender / makes me ill / I don’t like to think / of the texture of meat of bruises / shifting yellow when pressed”. Moving through the world like this, trying to be open and sweet, comes at a cost. I don’t think many artists are being honest about the toll it takes. After all, tenderness is the pain or discomfort when an affected area is touched, but it is not the same thing as the pain we perceive. If pain is perception, tenderness (medically speaking) is a fact. I guess I am saying writing this essay, like making most art, is the same as touching bruised skin. I am done with being tender because I can’t continue to press and then complain about being bruised fruit.

If we are part of a system where even art is shot through with capital, what does it mean to resist? Making art is not enough; making money is not enough.

Moving through the world like this, trying to be open and sweet, comes at a cost. I don’t think many artists are being honest about the toll it takes.

That evening, when the memory of that day had dissipated, I went to the gym. This is a habit I have adopted recently. The building is obscene in size and shape: a huge, air-conditioned rectangle. It is mostly men who go there, very muscular and distinguished looking – the kind whose résumés would read “excellent attention to detail”.

It’s clear I do not fit in. I am soft all over, and my attention to detail is average at best. My nail polish is always chipped. I put my headphones in before entering. As I walk past the cardio equipment to the weights room, people watch, or I perceive them to be watching, but I refuse to look up.

I have three workouts memorised, and I rotate them. All of them involve small precise movements with medium-sized weights. These workouts are about timing and form, not heaviness. I am meant to do as many repetitions per set as possible, within a time limit. I watch myself very closely in the floor-length mirror. I wear only black. If anyone enters my space or obscures my view, I place my weights on the ground and stand with my hands on my hips until they move. Everyone moves.

This space is fundamentally incompatible with so many of the values I have been trying to cultivate within myself: warmth, community, creativity. Connection with the natural world. Noticing the way light plays on leaves in the slowly vibrating trees. But something seems to have shifted. I have never felt more relieved to be in a clean, hard space; one that rewards repetition, solitude and physical strength. The clear guidelines, the bleaching effect of the fluorescent lights. Even the men, with their identical haircuts and polite but indifferent smiles. It has become weirdly soothing.

A peach bruises when its skin is compromised and can no longer keep oxygen away from the fruit. When air gets in, it starts to break down cellular walls and membranes, and the flesh begins to decay. Of course, to our eyes, the protective layer will appear to be intact. The bruise is not evident until you bite into it.

Later that night, when my own membranes are breaking down, I send a text I shouldn’t: “I miss you.” He would be asleep for the next eight hours, and in the necessary silence that followed, all I wanted was to be concrete. I felt sick. I opened the fridge the next morning and found peach juice dripping down the door.

So I am done with being tender. I will try to explain it again, more rationally:

tender

1. gentle, loving, or kind

2. painful, sore, or uncomfortable when touched

3. easy to cut or chew

The best theory I have is that I am coming up against the limits of what tenderness – as a philosophy, or way of life, whatever – can offer me. Walking around like an open wound is unproductive and frustrating.

Walking around like an open wound is unproductive and frustrating.

But when I re-read Holzer’s message now, I notice something I haven’t before: the first part of the line, IT IS IN YOUR SELF-INTEREST. It is a small shift that changes the frame completely. This is not a resistance to capitalism, but an acknowledgement of the fact everything has been infiltrated by it. Holzer from 1983 seems so confident about softness as a practice we all benefit from, but I don’t think we can entertain this as a truly tenable position. Not knowing what we know now. Not after observing a peach bruise and rot, split its own skin so juices spill down the fridge door.

Then again, I might be reading too much into a single phrase. Is this really what Holzer was saying? Of course, there are times when pressing into the bruise again and again becomes an act of narcissism. But if I am really honest, I think there is a better and more generous reading. Tenderness may be shot through with capitalism, but it is the only way I see true empathy remaining possible. So I send the text. I write the essay. I will cycle recklessly to the centre of the meadow, almost every time.

I guess I am lucky my heart has had such vigorous training, though I am increasingly unconvinced this metaphor is useful. I think tenderness must occur separately to how we feel, or we risk it become subsumed in narcissistic tendencies.

Other evenings follow that one, and then they keep following. On most, I go to the gym. I lift weights and put them down and am sore for many days after.

When I leave, the sun has set fully.