If you put your hand into a very alkaline liquid, like lye or bleach, the first thing you’ll notice is that it feels oddly slippery. Then you’ll notice that it hurts like hell.

That’s because bleach isn’t really slippery at all — you are. What you’re feeling is the fats and oils of your own skin being broken down to their constituent atoms by an alkali and recombined into new molecules. In other words, soap.

It’s not too hard to make soap. I picked up soap-making as a hobby a few years back, largely because I was depressed, which makes me hypercritical and quarrelsome. A do-it-yourself project, I decided, would be good. Something I could do with my hands, something that didn’t revolve around debate, critique, argument. You can’t argue with a bar of soap.

But there’s no such thing as doing it yourself; all the raw ingredients I used were extracted from somewhere, by someone, refined and packaged and shipped by a vast and unknown number of workers before I ever touched them. And everything speaks, if you know how to listen.

THE FAT OF THE LAND

I use rendered (refined) animal fat in my soap. This is unappealing to a lot of people, but it’s a traditional choice. I have a little plastic tub of the stuff in the fridge right now. It’s odourless, tasteless, and shelf-stable: a white waxy block I could pop out of the tub like an ice cube. It probably doesn’t even need to be in the fridge. I got it from a nationwide supermarket; it could be from anywhere.

Actually, though, it’s from round the corner. The manufacturer of this dripping is Peerless Holdings, in Braybrook, an industrial suburb in Melbourne’s West, not far from my own home in neighbouring Footscray.

This area has a long history as a centre of industrial production for Melbourne. In fact, Peerless Holdings acquired their Braybrook rendering site from Pridham, a renderer established in the 1890s. Then as now, it was part of a local cluster of slaughterhouse-related industries: butchers, meatpackers, meat canneries, candlemakers, producers of fertiliser, leather tanners — and soapmakers.

One of Pridham’s customers might have been Mowling’s Soap and Candle works, in the south of Footscray, closer to the mouth of Port Philip Bay. Built in about 1894 on the west bank of the Maribyrnong River, this complex of red brick buildings now houses a craft brewery, a martial arts studio, and a fish cannery. In its time, it consumed vast quantities of fat.

Usually, though, Mowling’s did their own rendering. A reporter from the local paper dropped by for a tour of the premises in 1899. A Mr Testo took him:

“to the tallow room, which is the alpha of everything. Here is heaped the refuse from the butchers’ tallow and all kinds of unsavoury offal. A lift bears this to a higher floor, where it is subjected to an immense hydraulic pressure, which removes the oil, leaving behind nothing but hard, stringy fibre, which is utilized for animal manure.

…Great vats of from four to six tons of boiling and bubbling tallow present the appearance of veritable miniature geysers of lava. These are then allowed to cool, and the finished soap is moulded into immense blocks, to be afterwards cut into the common or garden bar, to be stamped and wrapped by expert workmen.”[1]

Mowling’s best known soap brand was Empire Soap, packaged in a box with a map of the world on it.[2] A 1900 newspaper ad ran thus:

YOU DON’T SAY SO!

Yes! the sounds of martial tread.

And the dreams of EMPIRE spread.

Help remind us when we’re cleaning,

Of the article we need

And so far as merit goes

As the BEST for washing clothes

On MOWLING’S EMPIRE SOAP

We’re quite agreed.[3]

The primary competitor to Empire Soap in the local market was Velvet Soap, made by Kitchen and Sons in Kensington and Port Melbourne. Velvet Soap used the slogan “Velvet Soap Washes Linen Snow White”.

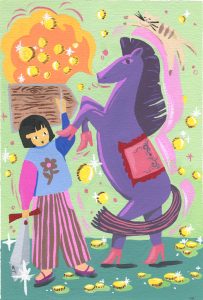

In one 1900s advertisement, an Aboriginal woman sits on an upturned box of Velvet Soap, scrubbing her sobbing child with soap. Patches of his skin are white, the black washed off.[4] On the right, another child stands, smiling; he is now white-skinned, with smaller, sharper features. Two smaller children, still Black, stand on the left, waiting their turn and weeping. The caption reads: “No use cryin’, ‘cos dat feller Barton says dis MUS’ be a White Australia”.[5]

It’s revolting, of course, but hardly unique. Soap has long been a symbol of British imperialism and white supremacy; the cleansing force of Empire wiping away the dirt of barbarism is a common motif in soap advertisements from this period.[6]

However, this imperialism was not purely symbolic. The Maribyrnong river was so foully polluted that fish and mussels were wiped out; even now, they’re not recommended for regular consumption.[7] On land, murnong and other edible tubers were cleared or trampled by cattle. All this meant sickness and starvation for many of the owners of that land, the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin alliance. Those who survived were forced into missions and stations; that is, into unpaid work for settlers.[8]

Even so, soapmakers couldn’t get animal fat at a good price; it was simply in too much demand. This was a problem. Any organic oil or fat can be used to make soap, but it’s not all good soap. Animal fat creates a hard soap bar, it’s ready to use pretty much straight away, and doesn’t turn to gloop in the shower; all highly desirable qualities. Not many plants can do the same, and those that can often have such low yields as to be commercially unviable. Except one: the oil palm.

PALMED OFF

Today, the world’s biggest producer of soap is British-based multinational company Unilever. Unilever owns Dove, Ponds, Vaseline, Impulse, Rexona, Sunsilk, Omo, Domestos, and a host of other brands in personal care, cleaning, and food. It’s extremely likely you ate or used a Unilever product today. (For me, it was a Weiss bar.) Unilever is also one of the biggest consumers of palm oil in the world.

Unilever was formed in 1921 by a merger between British soap producer Lever Bros and Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie. However, Lever Bros was a vast multinational well before the merger. Since 1899, Lever Bros had had a factory in Sydney refining coconut oil from their plantations in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. In 1914, Lever Bros bought a controlling interest in Kitchen and Sons; in 1924, Unilever acquired the remainder. As Kitchen had already acquired a number of other companies, this made Lever Bros/Unilever by far the largest soap company in Australia.[9]

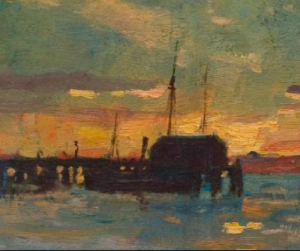

Promotional poster featuring global trade for oils, Lever Bros Sydney, 1900.[10]

While brothers James and William Lever were indeed business partners, the legacy of Lever Bros is primarily that of William Lever.[11] William was a lifelong supporter of the UK Liberal party, an advocate for imperialist expansion, and a control freak who played the long game — very successfully.

In the 1870s, Lever Bros invested in a newly invented method of making soap with a blend of vegetable oils, including palm oil. They called it Sunlight Soap. Sunlight Soap was highly successful, and consequently, production expanded so dramatically that Lever opted to build a new company town outside Liverpool: Port Sunlight.

Port Sunlight provided decent wages and conditions and housing for workers, green space, and a strict code of behaviour. It was an expression of the magnanimous and progressive employer Lever felt himself to be; perhaps somewhat paternalist, but in the way of a loving father. And its factories used palm oil farmed by forced labour in the Congo, under some of the most wretched conditions on Earth.

The Belgian colonisation of the Congo was infamously brutal even by the standards of nineteenth-century European imperialism. From 1885 to 1908, it was known as the Congo Free State, the personal colony of Belgian King Leopold II — not the Belgian state. While Leopold was a constitutional monarch in Belgium, he was an absolute dictator in the Congo.

In practice, the colony was mostly run by European private companies on land that had been parcelled out to them as concessions. On their concessions, they had all the power of a state, and all the support of the colonial military police — the Force Publique, a mix of Belgian officers, mercenaries, and Congolese conscripts. This included the power to demand forced labour, to set agricultural production quotas, and to punish those who failed to meet their quota with death. Most notorious was the requirement that conscripts account for every bullet by providing proof of death, usually in the form of a severed hand. If the soldier missed a shot, they might simply sever the hand of an unrelated person in order to escape punishment.

Eyewitness accounts of these atrocities reached Europe and caused a major outcry. It was during this period that Lever Bros was first attempting to negotiate a concession for the entirety of the Congo Free State’s palm oil plantations — a monopoly. In 1908, the Belgian state reluctantly took direct control of the Congo; Lever Bros got the concession they wanted in 1911. While some of the most outrageous and gory abuses slowed, Unilever continued to use forced labour in their Congolese plantations until at least 1945.[12]

Incidentally, Britain also had colonies in West Africa which produced palm oil. To access it, Lever Bros would simply have had to buy palm oil on the open market from African producers, at their price. They preferred to use forced labour — which continues to be a persistent problem in palm oil production.[13]

Palm oil is still sent from the Congo to Unilever factories in Australia; the closest to me is Tatura, Victoria. They’ve sold some of their trademarks, though: Velvet Soap and Sunlight Soap are still made in Shepparton, by another company. (They’ve been the same product for a while now, but the name varies depending on where it’s sold.)

Personally, I’ve never made soap with palm oil. While sustainably produced palm oil is available for sale, the actual supply chain can’t be reliably traced. It always seemed to me like the more ethical choice was to use animal fat; it seemed like making use of something that would otherwise be thrown away.

But really, I don’t know if that’s true. And I don’t know exactly where any of the fats or oils I use come from, or how exactly the workers who extracted them were treated. It’s impossible to find out, by design. These days, no large companies run every level of their own operation as Lever Bros did; it simply exposes them to too much responsibility, therefore accountability, therefore risk. They employ contractors, who employ subcontractors, who themselves employ subcontractors, and so on. Unilever itself no longer runs its own plantations. Experience has taught them that over the long run, it’s better to avoid the risk to their reputation. And they’re all about the long game.

Unilever has recently signed a pledge to ensure every person in its supply chain is paid a living wage. While this has been greeted with cautious optimism by labour and human rights NGOs, it’s impossible to avoid the thought that Unilever could guarantee a living wage for suppliers by bringing production back in-house. As always, this kind of pledge should be seen primarily as reputation management.[14]

I can’t know if a bar of soap was made ethically, even if I made it myself. As always, there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, or the extractive colonialism it demands. The invisible hand of the market is filthy with exploitation.

I do know this, though: a bar of soap isn’t just a mute object. No commodity is. It’s a microcosm of its whole world, the crystallisation of a set of social relations, a little chunk of extracted life force from exploited workers in far-off lands. A connection to the history under your feet.

—

[1] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/69678027

[2] https://www.picturevictoria.vic.gov.au/site/maribyrnong/miscellaneous/4746.html, https://www.facebook.com/metrotunnel/photos/a.2166694220219506/2218467168375544/?type=3&eid=ARDCTdb6QD-G5taLFsVgGCnZSYkqRfepYNCyAyE998Hjd7iW7JOoCktn5IpmsUVkn7aHE2y31ZAnLYf7

[3] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/241262275

[4] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/191708947?searchTerm=No%20use%20cryin%E2%80%99%2C%20%E2%80%98cos%20dat%20feller%20Barton%20says%20dis%20MUS%E2%80%99%20be%20a%20White%20Australia

[5] Edmund Barton, first Prime Minister of the newly Federated Australia.

[6] It’s worth noting here that like so much else, Europe owes soap-making technology to the Arab world; the word “alkali” is derived from the Arabic al-qaly, “ashes”. The highly alkaline ashes of certain plants were the original alkali used for soapmaking.

Other notable imperialist soap advertising campaigns were carried out by Pears and, of course, Imperial Leather.

[7] https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8601673

[8] Many Aboriginal people would later leave the missions and come to the area to work in the slaughterhouse industries. Pridham, the rendered fat company in Braybrook whose factory was acquired by Peerless Holdings, was well known as an employer of Aboriginal people in the 1930s.

[9] Mowling’s never became a multinational. The buildings were sold, and the company retooled. The last trace I could find of Mowling & Sons was as a bait supplier in the 1960s.

[10] https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-869218892/view

[11] I’m just going to call him Lever.

[12] For more on this, read Jules Marchal’s excellent Lord Leverhulme’s Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo.

[13] https://laborrights.org/industries/palm-oil

[14] https://www.raconteur.net/supply-chain/unilever-supply-chain/