There is a story my father tells me, of what he noticed when he dropped me off at a horse-riding camp when I was seven. It cost $100, and I remember that distinct lump of guilt when I thanked him – a lump that I came to assign to a larger, more unnameable debt. The word we so often use to describe this is sacrifice, which can sound so blunt, so kitsch. I’m thinking about my friend, who tells me her parents rely on sacrifice to show her their love. It’s not love, she says, when it’s not what you want them to do. I had never thought of this before, the idea of sacrifice as something we ask for. Somehow, I don’t think my parents would agree with it. They wouldn’t see generosity towards their children as a choice, as a deliberation of weighing up the pros and cons – more like something that compels, that moves them through space.

*

This horse-riding camp would be the first time I would be away from my parents, sleeping on a bunk bed. My father knew of the girls I was going to horse-riding camp with; they had names like Kate and Ashley, and when we visited each other’s houses, we would gallop and whinny, pretend the handlebars of our bikes were reins.

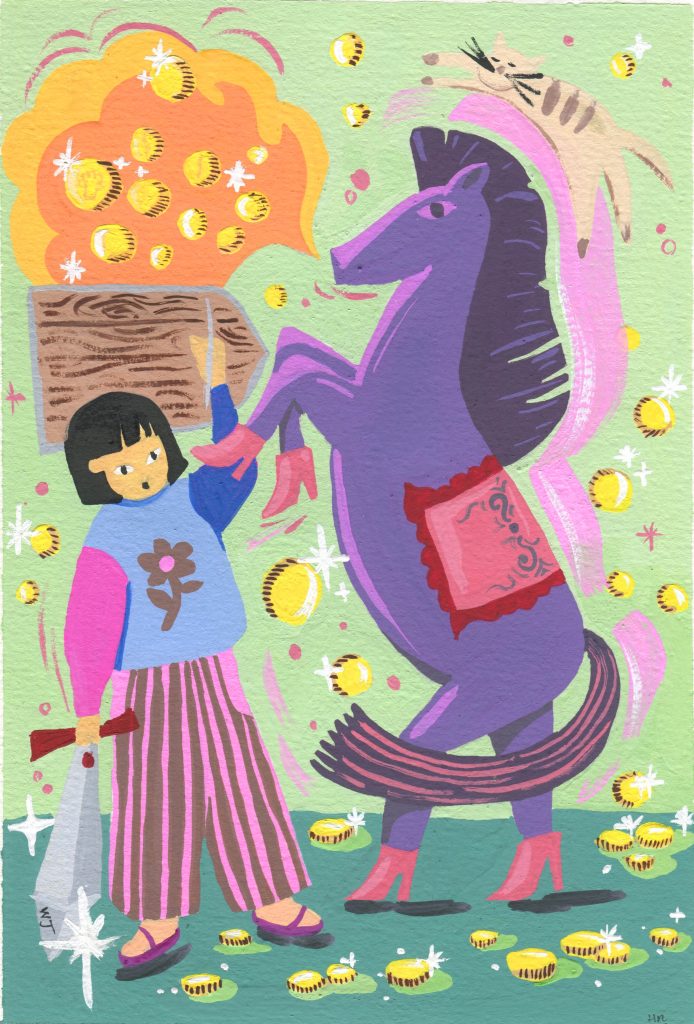

It started with the Saddle Club, which showed every weekday at 3.20 pm. Everyone wanted to be Lisa, because she was kind and pretty, but there was a self-assuredness about Carol; she was clear headed and could ride the best. When I started going to lessons at Mount Pleasant Riding School, I secretly named the horse I rode ‘Starlight’ after Carol’s. What I most looked forward to: the smell of burnt leather, being momentarily airborne over a jump, brushing down Starlight after a long day.

It was Kate who invited me to the camp, and at first, I told her I couldn’t come. Even now, this makes sense to me. There’s a line in Gregory Kan’s This Paper Boat: ‘I worry / that my parents’ answers are just another thing that I will be / taking from them.’ It was better to say no, to preempt any possibility of asking; camp would be just another thing that I will be taking from them. But my father, who was friendly with Kate’s mother, found out about it, and they talked, in the way parents do, through their children. Kate would be over the moon if Wen-Juenn came to camp, Wen-Juenn would love to come, etc. I don’t know why my father decided for me, but I think he suspected that I needed to be included. That my dreams were not only of rolling hills, or combing manes, but the act of staying up late, the confiding of secrets, the airborneness of galloping among friends.

*

On the night before camp, I left coins with notes attached in my parents’ bedroom. $100 could be spent on at least five Tamagotchis, or five horse-riding lessons, yet it was spent on a weekend camp for me. It felt luxurious, obscene. I envisioned them pulling open drawers to gold coins, spilling out. The coins, if anything, belonged to my parents. In my mind, it wasn’t so much to repay a debt, as it was to symbolise a gift. In Ladybird, a daughter asks her mother, in the heat of an argument, ‘How much?’ As in, how much did you spend on me, that I would need to repay you? How much, so that I have nothing to do with you ever again? It was the sort of pause that made my stomach ache. That night, I wanted the opposite; wanted my parents to feel my love in the form of uncalculated surprise.

*

Indebtedness, Cathy Park Hong writes, makes Asian Americans the ideal neoliberal subjects. How lucky, my mother will say, how lucky New Zealand’s immigration relaxed exactly when we wanted to leave – a slim window in 2000 – and that my mother was a teacher, basically a shoe-in. How lucky, that we can forget the Poll Tax of 1881, with £100 (equivalent to $20,000 today) imposed on every Chinese migrant arriving in New Zealand: one Chinese passenger allowed for every 10 tons of cargo. Instead, we are grateful, we work hard, keep our heads down, pay our debts to the state. The first Chinese migrant workers were recruited by the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce because of their inoffensiveness, their law-abiding, hardworking nature. My stay in New Zealand is just as conditional on being a worker, a consumer, my ability to make myself small and quiet. Weeping when I told my parents I couldn’t study law, couldn’t work full time, felt like robbery, like betrayal.

There are no stories of my mother counting coins, of my father working late. If anything, they give us unwrinkled, thick ang paos, fight over paying for dinner with family friends. They don’t believe in splitting bills, in calculating how much someone owes them. Both have the privilege of working in white-collar jobs – what more, their attitudes seem to say, could money give? If anything, I was the destined miser in the family – I found and stored coins, stashed shiny treasures in hidden places, became paranoid when things went missing, mourned the loss of a crisp note. There was the time my rose-gold bracelet slid off my wrist; subsequently, I relegated it to the safety of my bedroom, but would check up on it obsessively to reassure myself it was still there, still mine. Similarly, the weight of $100 grew heavy in me, and despite it being already spent, already lost, I stashed that debt and buried it safely in my mind.

*

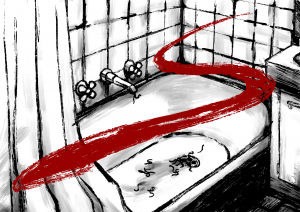

I cried during the nights. Not because I was alone, but because I was homesick. I didn’t want to sleep in a bunk bed, didn’t want to undress or brush my teeth, didn’t want to eat food cooked by strangers. If I had known this, I would still have gone. I would still have told my parents that it was fun. On the second day, during dressage, I fell off my horse. I gashed my chin, everyone gasped, and I hobbled to the building where the first aid kit was, where a nurse bandaged me up. At this point, my father – if he is telling the story – will begin to rage about the mismanagement of the camp, the absurdity that his seven-year-old daughter told him about her injuries before they did, how she walked the fifteen-minute walk to the main building, bleeding, on her own, while the dressage lesson resumed. Vaguely, I remember him lodging a complaint. These are things I have come to associate with my father: a bristling intolerance for unfairness, a willingness to call, to name grief as it is. It is this that makes me the way I am: non-confrontational, conflict-avoidant. It is because he has fought that I no longer feel the need to fight.

*

*

Recently, my father brought up the camp, but he said something he had never said before. I had to turn my face away, because I was afraid that if I looked at him, I would begin to cry. Sometimes, this feeling overcomes me. I am retelling a story, in control of the narrative, but with growing horror, looking at my friend, I will begin to melt, become porous and trembling. I was so angry, my father said, you were talking with Kate beforehand, waiting for the bus. But as soon as the bus pulled up—you know how children are like, rushing to their seats—she left you. Her first instinct was to find someone like her. And your friends, they were all sitting in their seats of two, and you had to sit on your own.

He waved, he told me, didn’t want me to think anything was wrong, but inside, he thought: how many incidents like this will happen, and my children will have to let it pass? He’s right that more incidents happened, that his children let them pass. But what moved me then was not my memory of the event – so much distance! So much time for this, of all things, to rise up like silt. And what if I deserved it? What if I was a horrible, spiteful child that Kate couldn’t wait to get away from me: please, I don’t want to sit with her. No, what moved me was my father’s painful remembrance of it, the first sinking realisation that his sacrifice was not enough to protect his children, to guarantee that they lived lives free of hurt.

*

I deliberately forget the feelings my father works to remember. He likes to excavate these memories as contributions to our dinner conversations, but there is nothing for me to do but admit that I was young, that I was made to feel excluded and different. These conversations leave me feeling simultaneously sceptical yet fragile.

Later, I remember him on the phone to Kate’s mother, telling her that he was extremely disappointed in her. It shocked me then, how my father spoke. That in admitting his disappointment, he was also admitting that he cared. His duty of care – to me, to Kate’s mother – could jeopardise his interactions with her from then on, but he did it anyway. So much of the care I have learnt is a politics of forgetting, assimilation, letting conflict become dull and lifeless. But care, he seems to think, means recognising that someone can act better than they have.

*

On WhatsApp, my father teases me about being a party girl – because I am unreachable. I miss his calls, I leave cryptic updates, I explain them later. In reality, I think he is relieved that his vision of me, young and excluded, didn’t turn out to be prophetic. But those fears are also mine, and they don’t dissipate. Stumbling, momentarily, upon my group of friends, feeling, for a moment, untethered, watching them laugh, appear at ease with each other, before one of them raises their head, looks at me and waves. Psychoanalysing why I fear large friendship groups, why I like my relationships diasporic and fragmentary, with a level of distance, a gap to let fallout happen noiselessly, without pain.

There are friends I still wish I could say something to; an acknowledgement of not-rightness. Not to reclaim feelings of hurt, but to lay the hurt down with some sense of finality; to put it to bed, to grieve. Some would call my father contrarian in his need to confront. But the other side of this is to flee, which I know how to do too well. To flee a conversation, a feeling, until I am left marvelling at my own hollowness. If I were to see Kate and those childhood friends again, I think I would tell them how nice it is to see them, then call my father, crying. Another part of me would want to unveil, take the tweezers and pluck the splinter out. I don’t know what I would say, but I know what I would feel – probably shame, at having spoken, and then relief. This is the closest I can get to speaking.

*

I know what will happen when I return home. There will be food already cooked, the heater will be on, and I will become irritated that my parents are everywhere. How everything will remind me that I will never not be a child in their presence, resuming, like muscle memory, to waking up with Radio New Zealand in the kitchen, my mother’s soft-boiled eggs left out for me, my clothes folded. But there is liberation in that knowledge: that I can always arrive to become a daughter again.

I never asked my parents if they discovered the coins or the notes I hid in their dressers, if they read my scrawling letters ‘THANK YOU MA AND PA’ and kept them somewhere safe. I never asked what they did with the coins, if they knew which ones were the ones I had raided and re-gifted to them, or if they bled into one another, ending up in parking lots, buskers’ hats, the collection bag during the offertory hymn. My parents continued sending me to horse-riding lessons, bought me Saddle Club poster- packs and mini-models of stables for my birthday – continued investing in a hobby that began to feel brittle and distant to me. Sometimes, I worry that it was useless, a waste. But then I remember the feeling of falling asleep in my mother’s Daihatsu, while she drove me home after horse-riding. How the afternoon sun heated up the car, how satisfying everything felt in that pocket of time. No, it wasn’t investment so that my odds in the world would multiply; it was so that I could encounter the awe, the bliss of something new.

In its early conception, all money started out as a promise: a pledge for the future, an infinite debt to society. In it, two people were bound inextricably in the most tangible but signified way – not only to themselves, but to the community which made such a debt possible, that silent third corner in the triangle of you, me, us. Now, debt is unwanted – the politics of who is constantly owing splinters any form of a generative future. Better to not owe anyone anything; better to be free. But sometimes, I imagine saying to a loved one, I am indebted to you. There is nothing I can do to pay you back. Perhaps it would gnaw at me, like numbers in a dwindling bank account, or perhaps it would feel like grace – like, momentarily, I’ve been forgiven before I’ve even asked.

Wen-Juenn Lee is a poet and editor who lives on unceded Wurundjeri land. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Meanjin, Antithesis, Landfall, Scum Mag, and Going Down Swinging. She still dreams of horses sometimes.

Henry Nguyen is a Kaurna land based communication designer and illustrator originally from Vietnam. His work is inspired by daily conversations and observation mainly on: gender politics, gender-neutral storytelling, the human-nature relationship, the self and folklores. Taking elements from those, his work takes shape in quirky creatures, colours along with a narrative reflecting my opinions in a way that speaks to him the most. @henry_creativ