For M

I was shortstop—number six—and already a little in love with everyone on the team, though it took me a lot longer to figure that out. The catcher was heron-necked, fingernails flecked with calcium and dipped in light. Centrefield had a too-quick, lemon-bright smile and a dimple on his left cheek. Second base had dark hair and darker eyes and freckles that glinted like mica.

Between games we watched the girls’ teams: their bronzed skin, sheeny hair, the smooth arc of their limbs. Or else we’d sneak off into the storm drains, cleats clacking like typewriters, where we found used condoms and nappies and pink Bic lighters and shouted just to hear our voices interlace and echo back at us. Once, we played chicken, venturing into darkness, and when I turned around, scared, I turned around to a chorus of: ‘Faggot.’

Sexuality, then, was split into binaries of straight and gay, vision and desire, certainty and uncertainty.

⁕⁕⁕

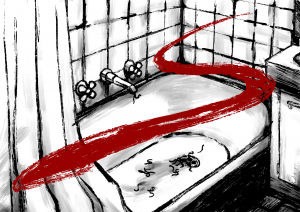

I only had one friend, then, who’d moved schools to be with me in high school. In year seven, in the changeroom after swimming, we took turns dressing in the single cubicle. I didn’t like being watched by anyone, and this anxiety overwhelmed any desire to look at others. Changerooms and bathrooms were spaces I dreaded entering. There, my body seemed to flicker in and out of existence but was also viscerally physical: it hunched under its own mass like a dying star.

While in the cubicle, the boys outside talked about me and my friend. My name, each time, came out sharp like the prick of a thorn. How does hiding your nakedness from naked boys become signified as queer? To hide is to be different. To be different as a boy, then, was to be signified as feminine. To be like girls was to like boys. To like boys was to not like girls. Bisexuality was not a word that we knew or cared to know.

⁕⁕⁕

Jack Halberstam writes about ‘the bathroom problem,’ where the gender binary is policed and reified through bathrooms and where sexuality is also maintained as heterosexual. People who do not conform to the gender binary (which rests on intelligible cisness and compulsory heterosexuality) are marked as both not-male and not-female, a subversive bothness which undermines gender. The violence that queer, genderqueer and trans people often face in bathrooms, Halberstam argues, leads from this undercutting of the gender binary which challenges sophomoric, reductive worldviews.

For the terms of gender to remain stable, Halberstam writes, ‘one must be readable at a glance.’ For one to be readable at a glance (especially then, in the mid-2000s) is to be marked as heterosexual. Yet, while gendered bathrooms are spaces of compulsory masculinity/femininity and heterosexuality, they are also places of queer desire and subversion, where men pickup/fuck men, and where the terms of gender fray from their own brittleness. It is this mixture of repression (the desire to be socially intelligible: to be a heterosexual man) as well as the potential for queer desire that, I think, made me most anxious: the sudden possibility to be found out or to do things wrong.

⁕⁕⁕

When I was eight or nine, waiting in a crowded queue for the public park toilets, I noticed an unlocked cubicle and opened it to see a young girl on the toilet. She seemed slightly younger than me; hair plaited with pink ties at the ends. Her face was round and pale, moon-like. The lock was broken. She didn’t make a noise, just sat there staring back at me until I slammed the door shut. Somehow nobody else had noticed. Or maybe everyone else was pretending not to have noticed.

I walked away saying nothing. At first, I was embarrassed. Then I was angry. What was she doing? Why was she even there? Why hadn’t one of her parents guarded the door for her? We had both broken rules, and I was burning up, red like a planet, with shame.

‘What’s wrong?’ Mum asked. I just shook my head. Then I wet myself on the way home.

⁕⁕⁕

Something almost holy happens to the body during sport. It’s the same thing that happens during good sex or when you’re gliding on the knife-edge of the perfect high: when your body recedes into the draped curtains of the world or else steps forward to where everything is brighter, more solid, so that when you roll your shoulders, the whole sky shifts, and the trees seem to sway with your breath. When you reach that flow state, it’s as if the world is a pendulum that moves as your body moves.

Imagine the body as lines of pure light which shift and shiver like static in relation to the world. The lines, at first glance, may seem flat, but are actually folded over themselves again and again like looped stitches in the universe’s cloak. When you are playing a sport well, there is some sort of continuum between these lines of light and the event of, say, the ball being hit and the body already, somehow, moving toward it. The physicality of sport makes these lines brighter, more visible. The body senses and is sensed.

Anxiety occurs first in the body, in the hands and the throat. Desire occurs first in the body, between bodies, in the fizzling, throbbing static between entities, a raised heartbeat, a widening of eyes.

Anxiety and desire have a closer relationship than most people think.

⁕⁕⁕

Long after I quit softball, when I dropped out of university and was first hospitalised for an overdose, the doctor wouldn’t discharge me because my heart was beating too fast.

‘It’s mostly fine now,’ the doctor said, ‘but his heart rate spikes whenever someone goes near him.’ Most of the doctors and nurses preferred to talk about me to other people. I remember, at one point, two nurses flirting while talking about my vital signs and their upcoming lunch break. At that point, because nobody had told me otherwise, I was still half-convinced I was going to die.

The next ECG’s results were elevated.

‘Are you anxious?’ The nurse had pale blue eyes, a shaved head and a nametag that said: Sven.

‘No,’ I said immediately, not knowing why, and we both smiled at each other because we knew it wasn’t true.

⁕⁕⁕

During a primary school chapel service, a boy pointed at my friend’s gracefully crossed legs and laughed. Instead of being angry at the boy, I was angry at my friend for drawing the boy’s attention, angry at both of us for being different. ‘Uncross your legs,’ I whispered. He looked at me, annoyed: ‘Why?’ ‘Just because,’ I said. Then, because he wouldn’t do it himself, I pushed his leg down, skin warm and soft beneath my hand.

⁕⁕⁕

I’ve written about softball before in a short story called ‘Takeaway.’ In it, softball is the major setting for the queer relationship between two women, Charlie and H, who nevertheless question gender and destabilise it in various ways. Why did I write this story between two women instead of two men?

⁕⁕⁕

In my state softball team, for every mistake we made during a game we had to run one pole—from one light post on the side of the field to the other. Halfway through I had an asthma attack. Gasping and crying, I stumbled to my dad who was sitting on the side of the field with the other parents. I took my puffs of Ventolin, the blue inhaler hard between my teeth, and sat on his lap while he stroked my hair, slowly calming me while my body relearned how to breathe.

A couple of years later, one of the parents who had been there was now my coach. When I made a mistake one game, he said: ‘Do you want me to make you run poles again?’

⁕⁕⁕

I became even more critical and perfectionistic about softball. After the games, I fixated on who did what wrong: who should’ve covered second base; how an outfielder missed me as cut-off and gave-up a run; how if I hadn’t fumbled a ground ball, I could’ve made a double play. My parents started taking turns driving me home after the games. One time I overheard Dad groan to Mum: ‘But I took him home last time.’

I couldn’t stop breaking down the game, focussing on every mistake, couldn’t stop feeling, no matter what, that the game was a failure, that I could have played better.

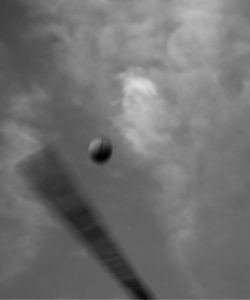

At about this time, when I was batting my anxiety peaked. Facing the pitcher, my body moved between being mine and being no one’s. It was hard to step with my front foot and drive, so I waited to be walked, occasionally half-heartedly fouling off a ball to spin in the dust in front of the dugout. If I made it to first base, I was relieved, but anxious about making a mistake running. I didn’t know how to slide, so I was always called out on 50/50s.

I was scared to learn to slide like I was scared to dive for the ball. During fielding my body was fully in control, on good days almost autonomous, and I didn’t want to—couldn’t—give up that feeling by pulling my legs from under me and throwing myself forward with abandon. Maybe, most of all, I didn’t want to look silly. I didn’t want to do anything the wrong way.

⁕⁕⁕

I was recently told that in primary school my parents got me professionally tested to see if I’d been sexually abused by a teacher or chaplain. I remember, vaguely, the appointment: a tall woman in a purple dress took me to a special office and asked me questions I don’t remember.

I asked my mother why, and she said: ‘Something was obviously wrong. We thought something must’ve happened to you to…’ She trailed off and took another sip of red wine.

I finished the sentence in my head: to make you like this.

⁕⁕⁕

In year nine (the number nine, coincidentally, is the final position—rightfield—on a softball team) somehow, impossibly, I forgot how to throw. All at once my body was stuttering and awkward, my throws slow and sloppy. I learned later that this is termed ‘the yips’ and is common across all sports. For almost inexplicable reasons (read: anxiety), athletes fuck up an action that, until then, has come as easy as breathing. There is some sort of hitch in minute body movements: something wrong in the way you step or the way your arm moves. Or maybe something wrong between steps, between movement.

‘You throw weird,’ another kid said at a tryout for some representative team.

‘I know,’ I said.

I did not make the team.

I started to dread the ball being hit towards me, and I added a glove-pump into my mechanics: field the ball running, take two steps, glove-pump, take another step and throw. It only slowed the inevitable: I still needed to throw the ball eventually.

⁕⁕⁕

In year eleven, I was invited to a distant classmate’s Halloween house party. I was anxious beforehand, dressed as a vampire in a flimsy cape and plastic fangs, worried that I looked ridiculous, worried that x would happen which might lead to y, etcetera. When it was time to leave, I had a panic attack. My dad lay next to me in my single bed and hugged me while I hyperventilated and cried.

‘It would be easy if I didn’t actually want to go,’ I said, slurring the words around the fangs I still hadn’t taken out.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘Shh, it’s going to be okay.’

⁕⁕⁕

I quit softball in year eleven. That same year, I kissed a boy for the first time.

⁕⁕⁕

I’ve been reading about Lucretius and the hardness of atoms and how to fall straight is to fall into nothingness, how everything swerves into each other.

Gender and sexuality are not immutable, nor are they absolutely fluid. This does not mean they do not exist in perpetual transformation, but rather that there are always singularities, relations of velocity and thresholds of intelligibility and crystallisation. When you reach a certain speed, Deleuze writes in The Fold, ‘a wave becomes as hard as a wall of marble.’ At certain temperatures, glass cools and hardens; it is both solid and liquid. The possibilities for sexuality are creatively infinite. Deleuze and Guattari write in Anti-Oedipus that the array of sexuality contains: ‘not one or even two sexes, but n sexes’ and n genders. While these infinite sexes and genders are narrowed by ‘overcodings’ of human-centred ontologies and relations of power—such as notions of family, economy and kinship—they cannot be fully closed off. Parts of us (and parts of us which are both not-yet and not yet us) escape towards creativity ad infinitum; there is always a point where the linear vanishes. All bodies are queer bodies.

⁕⁕⁕

I want to be like rain that includes lacunae of sky. I want to be the silver whirl of fish in a pond, where, as Deleuze writes in The Fold: ‘Not everything is fish, but fish are teeming everywhere.’ I want to ooze slow like glass. I want to be made of soft atoms which swerve and collide. I want to learn to be both.