Tree found the drive to Casino unpleasant. The paddocks she passed were depressing in their flat emptiness. The land had been desecrated by the arrival of non-Indigenous people like herself and the livestock they had brought with them. Just the odd scattering of huge trees now, partly uprooted and towering above small clusters of these nothing sheep. They disconcerted her. Why were they always like that? As if they’d been sucked out of the ground.

The shop, which was named ‘Second Life’ – in complete sincerity and ignorance of the online virtual world of the same name – was located on Hare Street away from the main strip of shops. Despite this, business was relatively steady. People came from all over for their peanut butter, which was ground fresh to order, and their juices, which were packaged in small glass bottles. Everything in the shop was expensive except the slices of banana bread, which were only $2 and even came heated with a delicious stick of butter that melted in the middle like a small, golden lake.

Like always, and despite the rain, she drove past the many empty spots right out front and parked around the corner along a residential street. She resented her job at the health food store at the same time as she found it soothingly disembodying and fascinating. Whereas at home her housemates stuck religiously to using the ‘she’ pronoun that she had first stipulated almost a decade ago, at Second Life she was called a mixture of Sir, Miss, Mr and Mrs, and even once read not as a full-grown proletarian at all but for a high schooler, because of her skin which had recently become pockmarked. As the oestrogen levels waned within her, they were replaced by an old testosterone force that rendered her skin the poster boy for her unstable mood. She didn’t mind the moods. She even caught herself thinking these highs and lows, underlined by the amalgamation of Sirs, Misses and Misters, were sometimes outright pleasurable. For the entirety of her adult life, beginning in her twenties and up until now (she was thirty-one) she had been an even-tempered woman. A disaffected woman. Disaffected by death, which she had met at an early age, and breakups even. Admittedly, she didn’t think she’d ever truly loved any of her exes as much as she’d simply liked them.

The glass door, recently painted with the words Second Life in what it pained her to know was ‘millennial script’, slid open with ease upon her arrival. Logan was a control freak and a workaholic disguised as a New Age hippie. He was so anal about setting up in the mornings and stocking the shelves in the afternoons that he both opened and closed the shop every day, only releasing the four hours in between to his array of casual employees. Everything down to the choice of the font on the door, which was written in a wispy, almost transparent silver, was researched, pored over and second-guessed. Logan seemed to make it a mission in his life to get the absolute best of everything.

When he would finally leave, relinquishing the computer and hopping on his bicycle, she would sit at the front counter and read through any tabs he had left open, and then she’d read through the history as well. Forum and Facebook posts on the best and lightest messenger bag, the best material for bed sheets, the best bike tyres for both gravel and bitumen roads. Thinking of purchasing a good tarp but need one with at least 4 tie points per square metre. Prefer silver. Don’t want to pay an arm and a leg, he would write.

The pleasure Tree felt when reading through his menial pleas levelled the playing field between them. Firstly, Logan was her boss, and though she thought him to be a loser she had to at least pretend to like him. This was degrading. On top of this, he persisted with a bit that poked fun at her name, as if her employment at the health food store existed entirely for his and his customers’ enjoyment. She’s called Tree! She was born for it, he’d laugh as he scanned the bone broth or the carrots or a packet of those fucking metal drinking straws, clearly never having considered that she might have actually chosen the name for herself aged twenty-two, nor that working in a health food store with such a name was not her ideal situation. And then came the: would you like a biodegradable bag?

Logan cared about the climate in the way that most small businesses did. He stocked KeepCups and tofu and cow milk alternatives, but in the storeroom he threw rubbish into whatever bin. Not that she cared. Green choices were for middle-class people who had an average amount of time to think. Too much time though, and the idea of it collapsed back in on itself and you found yourself throwing non-recyclable coffee cups into the recycling bin like Logan.

The only good thing about him was that he really did seem to care about whether she liked him more than he cared about her completing the banal tasks he left her stuck to the computer on a little Post-it Note each morning. He took fervent care to refer to her as a ‘she’, even going so far to politely correct customers when he heard them use something else. This however had the reverse effect. She found everything about him to be cringey: from his muscular calves that rippled down to a pair of Vans, to his wiry beard, hedging thin lips upturned almost permanently into a weak smile. She watched him closely in the hours they had together, which were thankfully few, collecting stories to tell her housemates.

Sol in particular loved these stories. He had a bitchy streak that came out with strangers only, and he listened with a smirk, eyes glistening eagerly. What she didn’t tell him was that for the last few months, every time she’d masturbated Logan had popped unsolicited into her head like a traumatic memory. They fucked in many different ways, but she was always completely naked and him completely clothed except for his penis, which, thin and ghostly, stuck out the fly of his jeans like the unearthed tree roots she saw on her way to work.

The image of his dick was still floating in her mind as the door slid closed behind her and she entered the shop, leaving a track of watery footprints on the lino. Logan was turning the kombucha labels in the fridge so that they faced uniformly forwards. Upon noticing her arrival, he snapped the fridge closed and turned his own body, with a similar beaming mechanical movement, to face her. Tree! Perfect timing. This man has just moved to town as well. He’s a painter. I was telling him about your gallery idea.

Logan always insisted on referring to Tree as having ‘just moved’, despite the fact that she and the others had been there over a year now. She looked around the shop. There was just one customer, a man with a mixture of mousy brown and greying hair who looked to be in his late forties or early fifties. He stood faced away from her, looking down at something she couldn’t see.

Mr, uhm. Sir. Logan had an irritating way of deferring to his customers as though he were a student and they his schoolteachers. He took a few toddling steps towards the man’s back. Sir, he said, louder this time, and the man turned. The first thing she saw was that he was dressed well, and by well she meant he was dressed somewhat stylishly. A brown jacket over a black t-shirt over loose navy pants that looked like they belonged on a tradesman over a pair of colourful neon green sneakers. The second thing she noticed was that he was holding a large yellow Lego block.

She was embarrassed. Her ‘gallery idea’ had been a project she’d been extremely excited about for exactly two days last summer, and in the foolishness of this feverish excitement had even told Logan about it. Just as quickly as it came the idea had gone away, evaporated by the realisation that such a thing wasn’t wanted or needed in the town. They had a gallery of sorts already, a coffee shop everybody loved that had artwork hanging inside. Who was she to come from the city and open a competing space in a town she knew nothing much about and in which she knew nobody? That had been her fake-humble reason not to do it. The real reason was of course that she was simply too scared to attempt to face her practice, which she had ignored ever since moving to Casino.

Oh, that was just a passing thought. Something to do here, she said, waving her hand as she walked towards the counter and ducked down to place her keys on the bottom shelf. Standing, she once again noticed the Lego piece in the man’s hands.

I found it under the herb stand. A child must have dropped it. He smiled and stepped over to the counter as well, placing it down on the black surface. Anyway, I think it’s a great idea. This town could use some more culture.

At this Logan frowned. Casino had a choir, several book clubs, a small cinema, and a pub that hosted live music. He knew it wasn’t much, but at the same time what more could a person want? Logan surveyed the two of them with an unfamiliar feeling: distaste. He rarely caught sight of his employee in this light. He knew she was from the city, but she had never before passed judgement on the small town he loved and called home. That judgement came now in the look shared between her and the newcomer, a look that said loser town, loser man, and worst of all loser shop. It was a look he’d been familiar with throughout his life, but a look that had come less and less in the years following the opening of Second Life. The shop had bought him the valuable place in the community that his parents before him had not had, and people treated him with respect.

He’d been through a lot, everyone in the town knew that. His father a drunk and an addict, his mother dead by suicide when he was eleven. He’d had his first cigarette at 9 and first drink that same day, trying to shoot rabbits with his uncle, who was neither a drunk nor an addict but was a big gambler. He’d had his first needle aged seventeen, but after a few long years of heavy use he’d given it up. Then his father too had died, cardiac arrest. Then less than six months later his uncle, car accident. He’d been left property and a modest sum. He’d opened the shop, he’d grown his beard, he’d stopped driving and started cycling. His body had become strong. He hadn’t met a woman he wanted yet but everything else had come good. He refused to be made to feel embarrassed by these people.

Well, I’m going to head off now, he said, without rudeness. Tree, the note’s on the computer. Not much today. It wasn’t like there had ever been much. Still, his staff treated his notes with the resentment of teenagers asked to empty the dishwasher. Haughty. Too good. Too important. When he’d first opened the shop, he’d had the idea that maybe someday it could become a co-op. He’d had high hopes. He’d watched some American documentaries about it but the law in Australia was confusing. At times it seemed even antithetical to such an operation, though he shook this thought off as paranoid. In the years following the opening he realised nobody he knew, and certainly none of his staff, had the capacity or the interest to care for the shop anyway. Not the way he did.

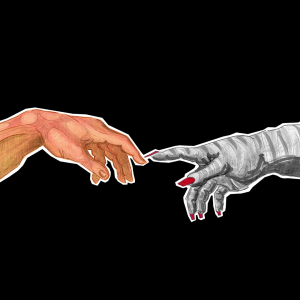

It was still raining when he stepped outside and unlocked his bike, his messenger bag cupping his hip comfortingly. He could see Tree talking to the stranger through the glass, but he decided he didn’t really care what they were saying. The man had said he was a painter (landscapes, he’d said) but his hands had been calloused and yellow like the Lego brick, like the hands of his own father. The hands of a tradesman. He couldn’t imagine them holding a brush with the delicacy he assumed such a thing needed. By the time he had organised himself and hopped on his bike, the man was leaving. He smiled at Logan, a real warm one. Then he waved, said seeya, and headed up the street.

Inside the shop, Tree watched the man walk away. To recall cruising was to recall a time before her disinterest in sex had taken full form. The memory of it was dull. It thrummed weakly, bringing with it the sound of a band playing in the other room, the feeling of coldness on her knees, the rhythm. At some point – she didn’t know when or why – she’d stopped noticing men. She knew you could have a conversation with, or even fuck someone without really noticing them. She’d done this. But she’d noticed this man, and she knew he had noticed her.