The house I grew up in was contained within two borders. At the back, beyond the sound of children laughing, lay the canal. Out the front, above the sun-bleached gate, stretched the telephone line. I could never decide which current I preferred.

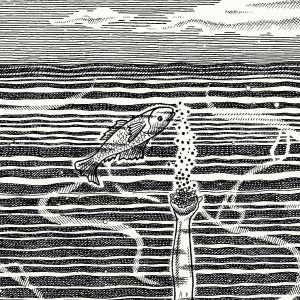

In winter, I’d watch the swell of refuse come rushing down from Ashfield, pick up debris at Petersham, before sailing past our backyard fence and emptying into the harbour. If the downpour was sufficient we’d place bets on which items might come swimming down the hill. Shopping trolleys always got the biggest cheer. Shivering on the concrete bank, we’d dare each other to traverse the muck after a storm. The ten-foot swim was a nightmare. Ducking sticks and fag ends you’d be pulled down past the Jones’, beyond even the Rasheed’s, before crawling up the stone embankment to safety. Dad was angry but we were sure he was jealous. That lustful summer of my fourteenth year brought visions of a teenage Venus floating in a shell on waves of ash-water. Pausing by the fence, she’d beckon me aboard and off we went. I didn’t tell my brothers that one.

My relationship with the wire was much more lonesome. I’d look up and wonder at the words whizzing within the hidden copper circuits. How many promises had been made and broken, how many joys and sorrows, flew above our heads I couldn’t fathom. Did all these electric sentiments end up somewhere like the rubbish in the ocean? Was there some vast expanse where news of Auntie’s death and calls to wrong numbers bumped innocently into each other like Coke cans and disused dolls on the high seas? When I heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch I thought “Oh yes? But where’s the great vortex of our voices down the wire? Show me the great pile-up of a billion conversations forgotten as quickly as that wrapper throw away.”

That’s what bothers me most I suppose. Despair, if you want, for the refuse. Cry foul, if you wish, for the waste. At least that great island of the discarded has itself for company.

If I had my time again I’d do this. I wouldn’t be heading out that front door with my phone to my ear and my shoe to the pavement. I’d be on that makeshift boat we made that time – five boards of timber and the bedsheet sail. Floating out I’d cry, “Farewell, Mr. Jones, and your children. And you Ms. Rasheed – please stay safe! I’m off on a little adventure! Don’t think me a stray or a waif!”